On Feb 25 night, fancy vehicles in large numbers were chock-a-block in whatever parking space was available along the side streets of the magnificent Mohatta Palace Museum in Clifton.

From federal ministers to foreign diplomats, dignitaries arrived in droves at the ceremony to mark the ‘comeback’ of the Yousuf Dewan (YD) Group of Companies in the auto sector, Minister for Interior, Planning, Development and Reforms, Ahsan Iqbal and Chairman Kolao Group Oh Sei Young among them.

The highlight of the ceremony was the unveiling of Daehan Shehzore, the successor to Shehzore pickup that Dewan Farooque Motors Ltd – the auto wing of the debt-ridden conglomerate – assembled in its 20,000-unit plant in Sujawal district until 2010.

This time around though, the light commercial vehicle is being relaunched as Daehan Shehzore following a joint venture (JV) agreement between the YD Group and the Kolao of South Korea in April 2016.

Apparently, the YD Group owes its reentry into the auto industry to the incentives it would get under the brownfield status that its auto assembly plant received through the Automotive Development Policy 2016-21.

But the real reason for the planned revival of its auto assembly plant is the expected cash inflow from the sale of Dewan Cement Limited (DCL) to Mega Conglomerate, a relatively new player in the country’s cement industry.

In other words, the billion-dollar behemoth of the pre-2008 era is now betting the ranch on selling one of its companies to pay for the revival of another.

If successful, the move can lift the whole conglomerate out of the default that, analysts say, is the biggest in Pakistan Inc’s 70 years of existence.

To have an idea of dwindling fortunes of the YD Group, consider this: Only two of the nine listed YD Group companies were trading at more than Rs10 a share on May 11. One of them was DCL, the company that the group is selling to revive Dewan Farooque Motors Ltd, the only other subsidiary trading above its par value.

Biggest default

According to one seasoned banker, who played a central role in helping the YD Group avoid total collapse or liquidation after 2008, the default amounted to Rs 55 billion.

The group, which originated in 1912 as a small company dealing in used garments, grew with few major setbacks until Dewan Muhammad Yousuf Farooqui started playing a more active role in business in the late 1990s.

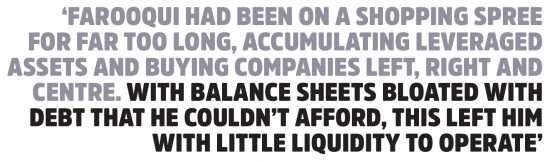

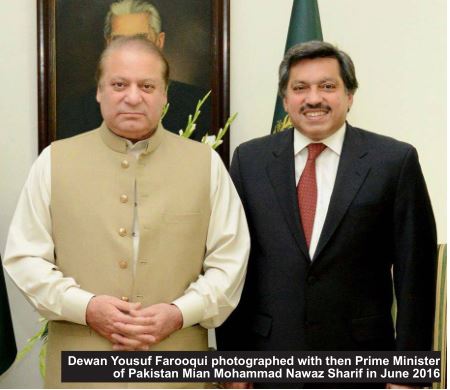

“Yousuf got close to Musharraf. He started expanding like nobody’s business. He went into too many businesses and got overstretched,” the banker said, requesting anonymity.

With the arrival of the Pakistan Peoples Party at the centre in 2008, the fortune stopped smiling on the YD Group. The new political dispensation tightened the noose around the neck of its chairman and cut him to size, he said.

At the same time, the global financial meltdown hit the cash flows of the conglomerate badly. Most of its businesses depended heavily on imported raw materials, like auto kits, coal and polyester. Banks revoked credit lines, and the group’s companies were left without working capital to run even everyday operations.

Farooqui had been on a shopping spree for far too long, accumulating leveraged assets and buying companies left, right and centre. With balance sheets bloated with debt that he couldn’t afford, this left him with little liquidity to operate.

The Dewan empire crumbled like a house of cards within two years. From posting a net profit of $5.8 million in 2005-06, the group went on to register the country’s largest-ever default in 2007-08. The number of employees decreased from 14,000 to 6,000.

The group went into negotiations with the banks. The State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), the banking sector regulator with a mandate to ensure stability in the financial market, forced banks to set up the steering committee to help minimise the loss arising out of the country’s largest default.

It decided that all the banks that had lent money to the YD Group would go pari-passu: an arrangement under which all creditors are regarded equally and repaid at the same time and at the same fractional amount as all other creditors.

In case a company that has used an asset as collateral for more than one loan goes bankrupt, its creditors usually get their money back based on their seniority. Those that lent it first take priority over others. “But the steering committee made a big concession in this case. Those banks that extended loans first made a sacrifice. That was a big event. It enabled the YD Group to survive by ensuring that banks stuck together,” the banker said.

Had the pari-passu arrangement not been worked out, banks with superior charges would have taken their money and vanished. The rest of the lenders with inferior charges would have been left high and dry, forcing them to go to court against the YD Group. “That would’ve upset the entire apple cart,” he said, adding that it was not a wilful default by the YD Group.

Rather, Farooqui ended up defaulting for his own doings. “He became aggressive and expanded heavily. He was like a bull in a china shop, picking up everything, opening all sorts of businesses without realising that he would need liquidity to run them,” he said.

The steering committee came up with a debt restructuring plan in August 2015 to the satisfaction of both the borrower and the lenders, according to a spokesperson for the YD Group.

Both parties agreed that YD Group companies would get financing to stand on their own feet while the past loans would be restructured to allow the struggling conglomerate some breathing space.

But the plan was suddenly shelved by banks for unknown reasons, the spokesperson said. He refused to comment on the possible reason for the banks’ unilateral decision against loan restructuring.

Analysts sympathising with Farooqui attribute the sudden collapse of the restructuring plan to the vested interests of lenders. Sponsors of the two of the four banks on the steering committee also own cement plants.

“They want the YD Group to either sell the cement business altogether or survive barely in the marketplace,” said one analyst. While the south plant of DCL enjoys proximity to the port, the north plant is the closest one to the under-construction Diamer-Bhasha Dam, which ensures steady sales for the next many years.

Cash cows

Of all his businesses, Farooqui seems to consider Dewan Farooque Motors Ltd to be one company that can potentially lift the pall of gloom that his empire has been enveloped in for the last decade. He’s apparently willing to exit the cement industry, which has grown phenomenally since 2013, to focus on the auto sector.

But his auto company has a major debt on its balance sheet. Its current liabilities exceed its current assets by Rs4.3 billion, which indicates the company is unable to meet obligations in the immediate term. In addition, the company hasn’t provided markup on its borrowings from banks amounting to Rs4.8 billion. Litigation for the repayment of loans amounts to Rs6.8 billion through attachment and sale of the company’s mortgaged properties.

So the only apparent way for the YD Group to revive the auto company is to sell another asset and use that liquidity to restructure its outstanding loans.

Farooqui has long maintained that he intends to pay off his debt. That’s why he sold his 51 per cent stake in Bawany Sugar Mills in 2010. He reportedly paid Rs5 billion out of the sale proceeds of the sugar mills to settle some of the outstanding debt.

As for the debt of Rs15 billion on the books of Dewan Salman Fibre Ltd, bankers are of the view that the company is a dead duck. It’s been out of operation since 2008 due to working capital constraints. There is no chance the company will escape liquidation.

Farooqui showed willingness to sell his cement plant around 2012, but found the price to be too low. The going rate for his cement plant was Rs7 billion at the time. “So he kept delaying the sale until cement became a big industry… a cash cow. Now that he’s selling DCL, he’s expecting to fetch Rs20 billion,” said the banker.

Background interviews with three people with direct knowledge about the workings of the YD Group suggest that it is expecting a price tag of around Rs28 billion for the cement company’s two plants. The share of the YD Group in the sale proceeds will be approximately Rs20 billion given its shareholding is limited to 75 percent in DCL. Retail and institutional investors hold the rest of shareholding.

After accounting for the bad debt on the balance sheet of Dewan Salman Fibre Ltd and the money paid back using the sale proceeds of Bawany Sugar Mills, the outstanding loans of the YD Group amount to roughly Rs35 billion.

In order for banks to restructure the remaining debt, YD Group must cough up around one-third of that amount, as per the State Bank’s prudential regulations. “So he’s going to give banks Rs11 billion while keeping Rs9 billion for reinvestment in his auto company and textile mills. He will become solvent once this deal concludes. His relationship with banks will be restored,” he said.

Resentment among creditors

Not all creditors are happy about the potential revival of the YD Group if the cement deal goes through. One institutional investor that put in roughly Rs200 million in bonds (term finance certificates) issued by one of the YD Group companies told Profit the leniency shown by the central bank in this case reeks of favouritism.

“Why didn’t the regulator go by the book in this case? The default happened 10 years ago, but very little recovery has been made so far. What’s so special about the YD Group?” said the company CEO requesting not to be named.

A capital market professional who witnessed Farooqui’s earlier failed attempt to sell one of his two cement plants to an existing industry player said the banks had deliberately thrown a spanner in the works. “They collectively decided against providing the potential buyer with liquidity for the transaction,” he said, adding that the unavailability of credit stopped the potential acquirer from striking the deal. “Who will dish out billions of rupees out of their own pocket to acquire an already debt-ridden company?” he said.

The latest bid to acquire DCL by Mega Conglomerate is partly financed by banks though. “Farooqui is a shrewd businessman. He’s been dodging 20 banks for 10 years. You think anyone else could’ve done that? He’ll survive,” he said.

The Mega offer

The share price of DCL started surging as soon as the word spread about a new investor showing interest in acquiring DCL.

The share price had increased almost 54 percent to Rs27.69 on February 1 when Mega Conglomerate, a group of companies operating in cement, logistics and real estate amongst other sectors, expressed its intention to acquire a substantial shareholding in DCL. DCL informed the stock exchange that Mega Conglomerate would soon start due diligence, a comprehensive appraisal of a business by a potential buyer.

In a letter on April 21, Mega Conglomerate Executive Director Aly Khan told Farooqui that the due diligence exercise established an ‘enterprise value’ of Rs27 billion. Khan acknowledged in the letter, seen by Profit, that the enterprise value is below the initial offer that the potential acquirer had made.

“This is due to the fact that historically DCL plants have produced much less than their rated capacities… As such, heavy investments are required to rehabilitate both of the company’s plants,” it said, noting that even the Rs27 billion enterprise value was “well above” the actual estimate furnished by the due diligence team to reach a workable solution for both the buyer and the seller.

On the face of it, the final enterprise value of DCL was not significantly lower than the price tag of Rs28 billion that Farooqui expected. But after making ‘adjustments’ and accounting for long-term liabilities and contingencies, the net asset value came to Rs15.26 billion. This means the 75 percent stake owned by the YD Group in DCL would amount to Rs11.45 billion.

Farooqui turned down the offer.

In his response to Khan on April 30, also seen by Profit, DCL Director Haroon Iqbal wrote that Mega Conglomerate had indicated that the enterprise value would be around Rs24 billion, with a possible revision of Rs1 billion either upwards or downwards as a result of the due diligence exercise.

But the post-due diligence offer by Mega Conglomerate was not acceptable to DCL for being too low – the sponsor of DCL apparently was not getting the kind of money it expected despite a higher enterprise value.

The share price of DCL was Rs22.75 on April 30, the day the company turned down the offer.

There has been no formal announcement on the stock exchange by DCL about the status of the deal. The DCL share price touched Rs19.67 on May 11, down 13.5 percent from April 30.

Against professional advice

The decision by Farooqui to walk away from the deal was against the advice of Next Capital CEO Najam Ali, the sell-side adviser appointed by the YD Group itself.

It should be noted that the appointment of Ali as adviser by the cement maker needed formal approval of his mandate by banks who expected to recover Rs6.1 billion from the Mega offer.

Next Capital reviewed the Mega deal along with all other offers that DCL received in the past. It concluded that the Mega offer was better than all the past ones.

Next Capital highlighted a number of reasons in its report, viewed by Profit, for the YD Group to go ahead with the offer. For example, it said the offer was tax efficient. The sponsor and other shareholders would get funds on a tax-free basis as opposed to the past offer by Bestway Cement, which involved a heavy tax on capital gains.

It also highlighted that the settlement of bank liabilities would be swift under the Mega deal because its structure required fewer legal procedures.

As for the bid by Bestway Cement received in February 2017 and withdrawn subsequently, it sought to acquire only one asset of DCL – its north plant for Rs11.8 billion. It would have involved a capital gains tax of Rs3.16 billion given that the company was selling an asset with a written down value of only Rs0.63 billion.

The proposed deal also had other complexities, such as the requirement that DCL should settle the debt of Dewan Textile Mills and Dewan Khalid Textile Mills from the sale proceeds.

Anhui Conch Cement, a Chinese cement manufacturer, had also shown interest in December 2016 to buy a 51 percent stake in DCL.

It proposed an enterprise value of Rs25 billion. After making various deductions, the final equity value came to be Rs13.58 billion.

Next Capital used multiple methodologies to assess different offers that DCL received in the recent past. For example, its working under the replacement cost method – a valuation technique that looks at the amount that an entity would have to pay today to replace an existing asset – showed Mega Conglomerate was offering Rs9,317 per ton as opposed to Rs10,352 per ton cost of new plant expansion.

According to Next Capital, even that methodology showed the Mega offer in a favourable light considering that the north plant is about 14 years old while the south plant is “quite inefficient”.

Other valuation methodologies like enterprise value per ton, equity value, enterprise value as a multiple of EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation) also showed the Mega offer was better than the rest.

Going by the then share price in the stock market, the total value of DCL was around Rs11.3 billion, substantially lower than the offer of Rs15.26 billion extended by Mega Conglomerate.

In addition to Mega Conglomerate, Bestway and Anhui Conch, Lucky Cement had also expressed interest in buying the north plant of DCL. It quoted an enterprises value of Rs10 billion.

Bids quoted by Fecto Cement, Cherat Cement and the Popular Group of Companies for the same plant were Rs12 billion, Rs11 billion and Rs12.5 billion, respectively.

Power Cement and EQ Partners, a South Korean private equity firm, also conducted due diligence, but didn’t make an offer.

Attock Cement, Engro Corporation, Master Group and Sapphire Group also forwarded their expressions of interest, but didn’t conduct due diligence.

All in all, 13 companies expressed interest, in varying degrees, in buying a stake (or asset) in DCL. Farooqui turned away each one of them.

Is he even serious?

“He uses the new-investor card to dodge bankers and the courts. He’s been dragging his feet on the issue of debt settlement for 10 years now,” said one analyst. He also accused the YD Group sponsor of siphoning off money from different businesses through cash sales.

At least two more senior bankers accused Farooqui of the same. “He will never sell DCL as long as he can continue to siphon off billions every year from it. Why else would DCL’s profit margins be much lower than other players in the industry?” said one suggesting that DCL is either understating its sales or overstating its expenses for the purpose. “He even manages to put pressure from different quarters to buy more time for himself,” said the other.

The spokesperson for the YD Group termed the accusations baseless, saying that the banks themselves bring potential investors to the conglomerate. “How can we fool the court or the regulator? Don’t our opponents engage expensive lawyers? Wouldn’t the regulator catch us if we indulged in corrupt practices?” he asked, rhetorically.

He insisted that the negotiations with Mega Conglomerate were still on. “We’re still in talks. The deal hasn’t fallen through,” he said.

Old habits die hard

A prominent businessman who has worked with Farooqui as a partner doesn’t think highly of him. “He doesn’t know how his businesses are run because his managers are running the businesses,” he said, requesting that his identity shouldn’t be disclosed.

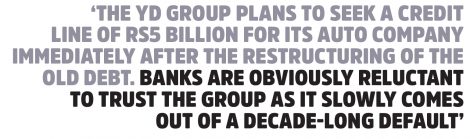

As a case in point in support of his argument, he said that after paying one-third of the outstanding loan, Farooqui plans to go back to the banks to borrow almost the same amount once again for his auto and sugar businesses.

“Bankers are wondering if he’s mad. I mean what would the banks get out of this then? They have already lost billions because of him” he said, adding, he had urged Farooqui to first invest part of the sale proceeds of DCL into his businesses, earn some profit and then show it to the banks to seek further financing.

According to him, the YD Group plans to seek a credit line of Rs5 billion for its auto company immediately after the restructuring of the old debt. The objective is to use that liquidity to import kits and assemble Daehan Shehzore pickups. Banks are obviously reluctant to trust the group as it slowly comes out of a decade-long default.

But he says the whole idea of seeking a credit line for assembling vehicles is senseless. “You already have a fully functional auto plant. Open a letter of credit for 90 days to import 600 kits from South Korea at the rate of $12,000. Use your dealers’ network of Shehzore, which already exists across the country, to get money in advance from customers. Rotate that money and assemble the vehicle in 45 days. Why do you need banks’ Rs5 billion for?”, said he.

Similarly, he said the YD Group is looking for another credit line of Rs3 billion for its sugar mills. “Instead, he can easily get a broker who’d give him liquidity to produce 5,000 tons of sugar and buy it at Rs45 a kilogram. He can then produce another 5,000 tons and repeat the cycle. But what can I say, if he wants to hoard now and sell during the Ramazan peak,” he said.

He recommended that Farooqui should borrow – if he must – from the banks against personal assets. For example, he should be able to get financing of up to Rs500 million against his house alone.

The YD Group spokesperson agreed that it was looking for working capital for its sugar and auto businesses. “Mobilising funds through auto dealers and sugar brokers is easier said than done. Some of our auto dealers recovered their 2008 funds in 2014,” he said.

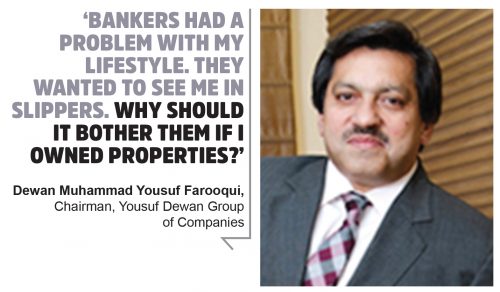

Despite going through rough times, Farooqui has been living life king size unapologetically, much to the chagrin of bankers – a fact he acknowledged in a 2014 interview with The Express Tribune.

“Bankers had a problem with my lifestyle. They wanted to see me in slippers. Why should it bother them if I owned properties?”, he was quoted as saying.

With the potential sale of DCL and a Korean JV partner on its side, the worst days of the YD Group may possibly be behind it. But how soon it succeeds in borrowing its way out of the country’s largest corporate default is yet to be seen.

Great article. We all use to think that senior bankers are shrewd and must know their businesses. But it is a myth. When the amounts (and stakes) are very high, banks dish out billions to big businessmen like Dewan just to grow interest income in the next 2 years. After that, even if the group defaults, who cares especially when there is no accountability?

Any banker with basic knowledge of credit would know that the business model of Dewan motors and sugar companies is such that it should not require any working capital financing from banks, as the customers pay in cash. However they will still give huge funding to Dewan Auto, just like they did in mid 2000s, just to meet their targets. Bankers will get away with it as both the regulator and the shareholders of the banks are sleeping.

What an interesting article however a bit biased towards bankers but yes truly seen ups and downs of the group and revamping is an interesting situation arising out of the decade. Lets see how this goes but commercial auto sales definitely do not run on cash and needs liquidity.

A great article.

Once a crook, always a crook.The real question is, has Pakistan learnt anything from the last experience? Or will they play in this crook’s hands yet again.

He sat quietly this long just so people forget what he did few years ago, and as a nation we do have a short memory.

It’s about time that regulators and if required Supreme Court of Pakistan to look into Automobile manufacturers profit margins, delivery issues leading to premium charge on vehicles.

The top 3 have been in the business for over 25 years and still fail to make correct projections or may be intentionally create a shortage and disbalance between demand and supply.while ordering CKD kits.

These shrewd businessmen know what they are doing and they have been getting away with this nasty game for a long time now. The Car Prices Are Ridiculously high, Imagine piece Of Junk Like Mehran is being sold for over 700,000.

Toyota Corolla is nothing but plastic and with low quality sub standard material making profits in billions. Honda Civic is priced at a King’s Ransom with fuel consumption of 4000 cc Engine.

Unless some one puts a leash on

“The Three Profiteers” they will continue to rob the customers.

Eye opener for both teams.

Interesting and insightful. Well researched and very well written.

Clearly sponsored. Mr. Kazim for those who know the story behind this article wont appreciate your efforts. If you really want your audience to believe in what you have written then show some guts to write some thing about the other side too. The political interest and some big guns in the banking sector who are interested in this empire.

Sponsored article!!

Farooqui is the Pakistan equivalent of vijay maliya.

Agreed ! it seems that article is 100% sponsored.

first of all this picture should not be used, it gives an image over panama leaks look. secondly the guy was stopped for doing business for years, stake holders, investors, employees they all got effected, but still he stand up with an some old team and got into where they left from. lets hope for the success, eventually people are back to work at least.

Comments are closed.