It was among the biggest failures in Pakistan’s financial services sector: KASB Bank, the retail bank owned by the KASB Group had been dying a slow death since the financial crisis of 2008 but was finally euthanized by the State Bank of Pakistan in November 2014. An unexpected casualty of this was KASB Securities, one of the most venerated names on McLeod Road and the oldest functioning capital markets firm in Pakistan until that point.

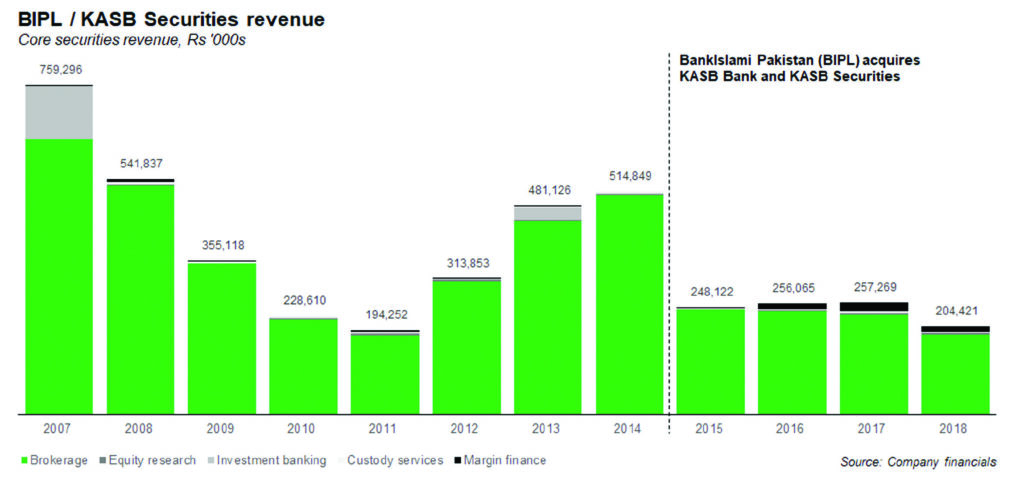

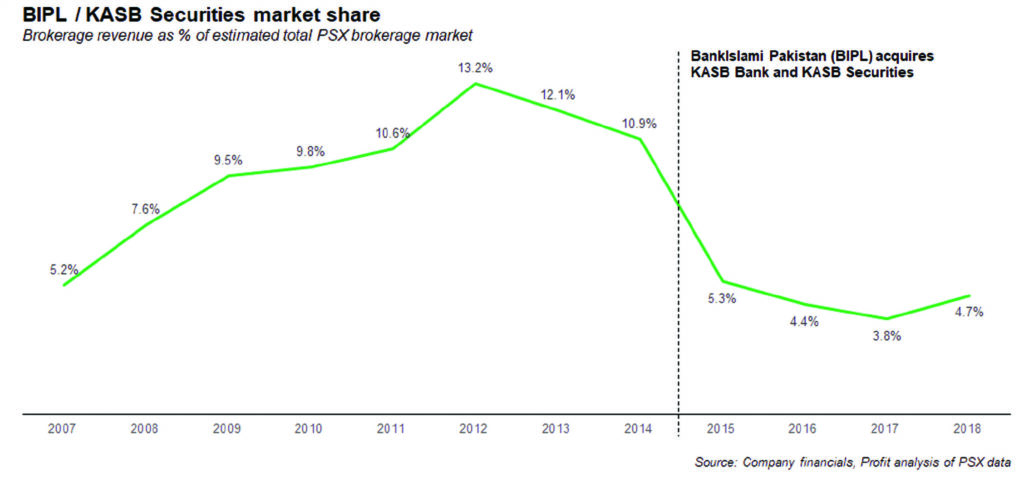

KASB Securities did not quite die off. When BankIslami Pakistan (PSX: BIPL) acquired KASB Bank in May 2015, they received 77% of the shares in KASB Securities as part of the package. But BIPL is hardly known as a capital markets powerhouse, and KASB Securities – renamed BIPL Securities in November 2016 – began losing clients almost immediately and currently does only about half the business that it used to under the old KASB name and ownership.

Between 2016 and 2018, it seemed that the KASB name was lost, buried in the long line of erstwhile venerated brokerage houses and investment banks that have since passed into history: the likes of Barings, Saloman Brothers, Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, etc.

But then came the news in April 2018 that all may not be lost just yet for the KASB brand. A new brokerage firm – named Khadim Ali Shah Bukhari Securities, and using the old KASB logo – was launched that month. Its managing director was a 37-year-old finance professional named Ali Farid Khwaja.

This then begs the question: who is Ali Farid Khwaja and is KASB Securities really back? More importantly, why does KASB matter to Pakistan’s capital markets?

Why KASB is a valuable name in Pakistan’s markets

Quite simply: because they were among the very first in Pakistani history, and one of the very few to have survived nearly all of the booms and crashes to have hit the market throughout Pakistani history.

The company was founded in 1952 by Khadim Ali Shah Bukhari, then a neophyte to the nascent securities industry in South Asia. Back then, the idea of corporate brokerage houses was practically nonexistent, and so Bukhari operated effectively as an individual, offering stock trading to clients – both individual and institutional.

In the 1970s, in the ethnically divided world of the Karachi Stock Exchange, where it was the Memons (Gujarati Muslims) versus everyone else, KASB & Company – the ethnic Punjabis with a long history in Karachi – were able to grow big enough on their own. The Memons never trusted them as part of their circle, but the Bokharis were given a begrudging respect that Jahangir Siddiqui, the ethnic Sindhi insurgent, never got.

The real modernization wave, however, did not start at KASB until Khadim’s son joined the business in 1977. Then just 20 years old, Nasir showed an acumen for the business and a clear head for strategy that his father had the good sense to allow him to implement. Core to Nasir’s strategy: build out a large retail book of business by going out and establishing branches all over Pakistan.

This strategy, however, would need the market more modern than it was, a task that Khadim and Nasir would not be able to achieve on their own.

In the late 1980s, Nasir formally took over the business and he and Jahangir Siddiqui, that other innovating buccaneer of the Karachi Stock Exchange, became close friends, united by their relatively better education which spurred their desire to drag the Pakistani capital markets out of the nineteenth century and into the late twentieth.

Both Nasir and Jahangir decided to take the plunge themselves first, incorporating their brokerages from sole proprietorships to public limited companies. Nine years younger, Nasir was a key ally for Jahangir when he sought – and won – the chairmanship of the Karachi Stock Exchange in the 1990s.

Throughout the 1990s, both JS and KASB had very similar trajectories. Both brokerages sought relationships with American investment banks, JS with Bear Stearns and KASB with Merrill Lynch (in 1994). Both incorporated in 1991 and listed their companies on the exchange by 1993. And both consistently pushed the exchange towards modernisation, backing ideas like electronic trading, which would be necessary for Nasir’s idea of a nationwide retail brokerage operation.

They ultimately got their way with the introduction of electronic trading on the exchange beginning in the early 1990s. That, in turn, allowed Nasir to build out offices throughout the country, and he opened up KASB Securities’ branches in 11 cities across the country and began offering electronic trading platforms.

KASB was also among the very first brokerage firms in Pakistan to embrace the internet, allowing retail clients to trade, first through their website and desktop software, and then through mobile apps.

That retail, individual investor-friendly business model made KASB the largest retail brokerage in the country, and the largest of any kind by trading volume. At its peak, shortly before its sale to BIPL in 2014, the company boasted 22,000 clients and a 15% share of all trading on the Pakistan Stock Exchange.

And the high quality of research through its partnership with Merrill Lynch – as well as trading execution – meant that KASB was widely regarded as the best brokerage firm in the country, a status epitomized by the fact that AsiaMoney, the London-based publication, rated KASB Securities the “Best Equities House in Pakistan” for 24 consecutive years, from 1990 through 2013.

Simply put, if you were a retail investor in Pakistan in the 1990s or 2000s, you could not do better than being a client of KASB Securities.

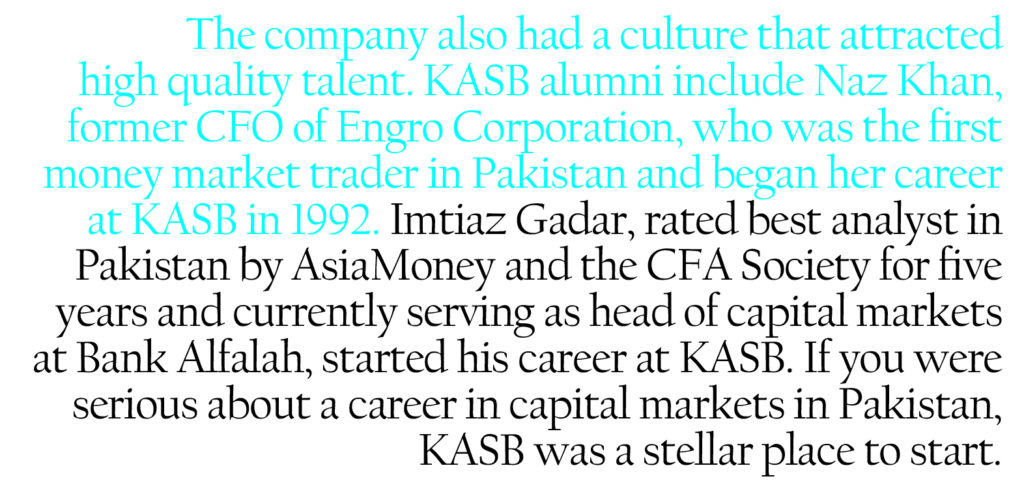

The company also had a culture that attracted high quality talent. KASB alumni include Naz Khan, former CFO of Engro Corporation, who was the first money market trader in Pakistan and began her career at KASB in 1992. Farrukh Sabzwari (chairman of the Securities & Exchanges Commission of Pakistan), (Muneer Kamal, chairman of National Bank of Pakistan and the Pakistan Stock Exchange), Ali Sultan (treasurer at Bank Alfalah), and Imtiaz Gadar, rated best analyst in Pakistan by AsiaMoney and the CFA Society for five years and currently serving as head of capital markets at Bank Alfalah, all started their career at KASB. If you were serious about a career in capital markets in Pakistan, KASB was a stellar place to start.

How it all went wrong for KASB

For most of the 1990s, Nasir stuck to expanding his brokerage business but slowly became convinced of the idea that he needed to acquire the ability to lend in order to retain clients who wanted margin financing.

In 2002, a small Pakistani bank named Platinum Commercial Bank ran afoul of the State Bank of Pakistan’s minimum capital requirements. The SBP had set the requirement then at Rs1 billion and Platinum was only at Rs600 million. Pak-Libya Holding Company, a development finance institution funded by the Libyan government, initially offered to buy the company but that transaction fell through.

At that time, the newly empowered Securities and Exchanges Commission of Pakistan was cracking down on the informal margin financing system known as “badla”, which was hurting the business of several brokers, KASB included. Nasir smelled an opportunity in Platinum’s distress. He began buying shares in Platinum, eventually purchasing the majority stake.

Nasir saw Platinum as a source of formal margin financing for his brokerage firm. At least initially, he was not thinking of it as a means to expand his capital markets business into the banking industry. But he was keen to get his family name onto a licensed bank and so, in February 2003, he merged his brokerage holding company with the bank, and renamed it KASB Bank.

As may be obvious from the way KASB managed to acquire the bank, KASB Bank initially had no real strategy. Unlike JS Bank and BankIslami, which were at least deliberate forays into the banking market by previously capital markets focused companies, KASB Bank’s initial purpose was to provide KASB’s brokerage and fledgling investment banking business with a balance sheet. Also, soon after Nasir relocated to Singapore, visiting Pakistan only occasionally.

Nonetheless, having acquired the bank, KASB at least tried to give its bank some semblance of a strategy. In 2005, the bank embarked on an ambitious branch expansion, opening 14 branches to take the total number up to 35. That sudden burst of expansion, naturally, led to an increase in the bank’s operating costs, which in turn caused the bank to have a net loss of Rs205 million in 2005.Perhaps it was the loss that scared the management, or perhaps they decided to consolidate before further expansion, but KASB ended up not opening any new branches for two years after that.

On the asset side, meanwhile, by most accounts, KASB Bank does not appear to have quite mastered the art of lending money. While the loan portfolio’s infection rate was in the 4% range up until the beginning of 2008, that appears to have been a mirage. KASB Bank’s clients were small businesses who appear to have borrowed from the bank a lot more than they should have and when trouble hit – as it did in a big way in late 2008 – they were simply unable to pay.

Yet even without those losses, by 2007, it was clear to KASB that its asset base was not big enough to support the bank’s operating costs. And so, the bank started on what can only be described as a poorly timed expansion spree.

In 2008, right when the world was collapsing on banks and the entire interbank lending market completely froze up, KASB Bank more than doubled its branch network from 35 to 73, adding 38 branches that year. Of those, 28 branches came online in the fourth quarter of 2008, the worst possible time to have your operating expenses grow.

As expected, around that time, KASB Bank’s loan book simply blew up. This is not hyperbole on our part. The infection rate on their loan portfolio jumped from 4.0% in the third quarter of 2008 to 17.8% the very next quarter and it pretty much never looked back since, jumping to 21.6% the following year and 27.1% the year after that.

KASB had the worst luck imaginable. Just as they were kicking off their big expansion plan, their loan book blew up, taking down with it any chance the bank had of surviving as an independent entity.

KASB Bank was bleeding money at this point, with a net loss of Rs1.4 billion in 2008 and Rs4.3 billion in 2009. In a single year, the bank’s losses had wiped out almost half its equity. For much of this time, the bank had to rely on extremely expensive deposits that effectively rendered its net interest margin negative. But the bank’s board and the management kept going with his expansion plan, opening 31 new branches in the second half of 2009.

By that time, KASB Bank was completely done for. Between the third quarter of 2008 and the time the State Bank of Pakistan officially euthanised it in the fourth quarter of 2014, the bank lost an astonishing Rs13.4 billion. In the last six years of its life, KASB Bank had only four quarters of positive net income. The rest were all brutal losses.

Both the SECP and the State Bank had been repeatedly telling KASB to get its act together and shore up its capital reserves. All other banks with MCR violations were at least making the effort to raise capital. Nasir and the KASB management, unfortunately, seem to have been either unable or unwilling to do so. The problem had gotten so bad that the International Monetary Fund repeatedly warned that KASB Bank constituted a threat to Pakistan’s financial stability.

By November 2014, the State Bank had heard enough excuses. They moved in and put KASB Bank into receivership. (It was also the first time Pakistanis realised that there was such a thing as deposit insurance in the country, that covered all bank accounts up to Rs300,000.)

In December, Nasir tried to get some Chinese investors to pump in money, but the investors did not pass the State Bank’s sniff test. They were not able to specify their beneficial ownership, nor even explain how they planned on pumping $100 million into the bank. And so KASB was put on the auction block.

In February 2015, Nasir sued the SBP, trying to get them to at least let him participate in the auction as the selling party, but the State Bank was not interested and he dropped it after some conversations with the SBP.

Four banks began the initial due diligence process: BankIslami, JS Bank, Sindh Bank, and Askari Bank. On closer examination of KASB’s books, the latter three dropped out. Deloitte, which was brought in to conduct a full audit of the bank and assign an accurate book value to the bank came back with a number that was so deeply in the negative that the State Bank refused to make it public and instead sold it to BankIslami for a token amount of Rs1,000 for the whole thing.

The merger was completed on May 7, 2015.

Unfortunately, while the KASB group was moving away from their core strength of equities trading and brokerage, in 2010, they also made the mistake of making KASB Bank the holding company for their shares in KASB Securities. That meant that when they lost control of the bank, they also had to surrender control over KASB Securities to BankIslami.

The KASB Securities comeback

But while the foray into banking damaged the Bukhari family’s finances, it did not sully their reputation for being the best equities house in Pakistan. Indeed, KASB Securities’ clients have continued to move away from BIPL Securities in droves, with 8,000 of the 22,000 clients having already left the company, and the remainder reducing their trading volumes with the firm.

Needless to say, that left opportunity ripe for the plucking. And in stepped Ali Farid Khwaja to capitalize on it, in collaboration with the younger generation of the Bukhari family.

“There was a space in the market, and the goodwill that the KASB name still inspires,” said Khwaja, in an interview with Profit.

Khwaja grew up in Rawalpindi, attending St. Mary’s Academy before pursuing his bachelors degree at the Lahore University of Management Science (LUMS), graduating in 2003 with a degree in economics and computer science. He worked in Karachi for a year as a research analyst at AKD Securities and Alfalah Securities before going to Oxford University to study on a Rhodes Scholarship.

After Oxford, Khwaja went on to work as a securities research analyst in London for about a decade, also leaving to become CFO of a European technology company before creating Oxford Frontier Capital, an investment vehicle that he used as the platform for his investment in the newly reincarnated Khadim Ali Shah Bukhari Securities.

The new KASB is owned in part by Khwaja and his co-investors who have brought in approximately $2 million into the company. At least 60% of the company remains owned by the Bukhari family. Khwaja himself is not a stranger to the family, however, since he is Nasir’s son-in-law. Khwaja serves as a managing director at the company. The CEO is Mahmood Ali Shah Bukhari, Nasir’s son.

Khwaja’s vision for the new KASB involves the company having two separate business lines, though both harken back to the original strengths of the KASB franchise. The two business lines would serve two different types of clients: domestic Pakistani retail investors, and foreign institutional investors.

For the domestic Pakistani retail investors, Khwaja envisions building a platform akin to the biggest names in global fintech. “Our desire is for KASB to move into the fintech space. So that is the play for us. We want it to be a dominant platform for digital wealth management in Pakistan,” he said.

“So far, we have relaunched K-Trade [the name for KASB’s old mobile and desktop trading software]. And we want to grow to have a more sophisticated investor base,” he said.

On the retail front at least, the company appears to be gaining some early traction. In just over a year since it launched, KASB Securities has 130 clients and manages just over $2 million in assets. “We have been the fastest growing broker in Pakistan. We have gained a 2% market share even though we have just been setting up our infrastructure,” he said.

For the foreign institutional investor base, Khwaja has decided to remain based in London in order to continue building out that book of business. “The clients are international, so I am based abroad to stay close to investors. I live in London, but I am in Pakistan every couple of months,” he said.

And he has recruited Madiha Alam, a high-flying trader with experience at several bulge bracket investment banks in London, to help with the effort of attracting more foreign investors to consider Pakistan’s equity market as a destination for their investments, and to use KASB Securities as their platform for doing so.

But Khwaja and his team are not done yet. They are seeking additional capital to build out the company’s technology infrastructure in addition to building additional capabilities to help it serve both of its end markets. Khwaja has been flying around the world, seeking investors in both KASB Securities as well as the Pakistani capital markets.

If brand pedigree is anything to go by, KASB Securities has much to build upon, and in Khwaja, they appear to have found a capable executive dedicated to reviving that residual goodwill. It is too early to say if KASB will ever become the capital markets powerhouse it once was, but it certainly appears off to a strong start on its road to a comeback.

Usefull but I need full information about kasb.

Sir my father was died at 3 nov 2012 and account on KASB with joint ac holder me and know about it but i cant open my individual account in that branch but how to possible open and in statement after death date some funds tranfers till 2014 and in statement last written instruction deposits/ instrument which remain inoperative for a period of ten years shall become un claimed and will be surrended to SBP as per the provision of BCO… kindly can somebody guided me about this and where i go first to mark complain and check overall person bank takaful insurances

Comments are closed.