In an article published last year in Dawn, writer Khurram Husain had assessed that under the Supreme Court’s “Dam Fund” announced by then-Chief Justice of Pakistan Saqib Nisar, it would take 199 years to raise Rs1.45 trillion needed to build the Diamer-Bhasha and Mohmand Dams at the highly unlikely pace of Rs20 million per day.

A year has passed and the project has fallen off the headlines, with Rs11 billion collected so far. At this speed, the construction of these dams through crowdfunding appears impossible and the water crisis that prompted the Supreme Court and the Prime Minister’s Office to launch this scheme continues to grow larger and larger with each passing day.

So, what can be an effective way to deal with this crisis or at least mitigate it? Proper water management and efficient use of water in agriculture are considered viable solutions, as are wastewater treatment and recycling that can help reclaim water. In industrial use of water, technology can make a real difference: ozonizers (or ozonators) and the Molecular Distortion Technique can help conserve water by at least 70%, according to Aqua Water Technologies Managing Director Asif Ahmed. Another source with an interest in applying this technology told Profit that it could reduce water use by as much as 90%.

The ‘looming’ crisis

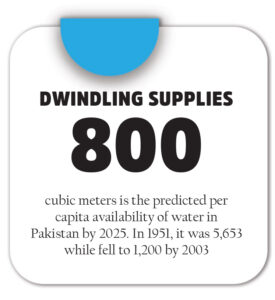

In 1951, the per capita availability of water in Pakistan was 5,653 cubic meters. By 2003, it had fallen to 1,200 cubic meters against the international standard of 1,500. Predictions suggest that by 2025, per capita availability in Pakistan will decrease to a shocking 800 cubic meters only.

Moreover, competition for a basic resource like water is increasing with the steady rise in population, urbanization, and industrialization. According to a study conducted by researcher Salim Khoso, 23% of available water is used by industry, eight percent by domestic users, and whopping 69% goes to agriculture. Another research study shows only an upward trend in the use of water, in both domestic and industrial contexts, to an average of 15% of available water resources by 2025. In 2000, domestic and industrial use was just three percent of available resources.

It shouldn’t be news to anyone reading this that Karachi, the country’s largest city and the economic hub, is facing an intense water crisis. It is almost old news, at this point. Sindh Local Bodies Minister Saeed Ghani says that the city is facing acute water shortage as it receives about 500 million gallons per day (MGD) but its demand is more than double that amount: 1,100MGD. This means that a majority of the city’s population could go a day or more with no or low water supply.

Can ozonization solve this situation? It’s hard to say definitively, but it can certainly help alleviate the shortage. Here’s how. The city’s wastewater accumulates to 460MGD and 40% of this water can easily be reclaimed for non-domestic use like horticulture or cooling/boiling agent in industry, says Dr. Noman Ahmed, chairperson of the Department of Architecture and Planning at Karachi’s NED University. At the moment, only a meagre 66MGD is treated and industry uses fresh water for cooling needs when recycled or grey water can just as easily do the job. (Grey water is what goes in the sink as compared to black water, that comes out of sewage.)

The situation isn’t much better in Lahore, the second-largest city. “Only three big companies from the textile industry use more water than the amount used for domestic purposes in this city of about 12 million people,” says Mohammad Zaid, co-founder of Save Every Drop (SE Drop) – a startup working to make filtering and recycling of wastewater economically-feasible.

Industrialists vs. innovators

But sources tell Profit that there is resistance among industry leaders to embrace ozonization. “The ‘seth’ mindset prevalent in the industry, especially in the textile industry, has been hindering the use of new technologies to recycle water,” says one employee, on condition of anonymity as they are not authorized to speak to the media. “Other governments actually bind manufacturing businesses to use wastewater treatment techniques to make sure that water is efficiently used and not wasted with pollutants. But here, the Seths tell us that they have enough water and they don’t need a new expense.”

It is for certain that water is scarce, not just in Pakistan but throughout the world, and denial of that fact will only cause Pakistan to lag behind in adopting new technology for water reclamation. Some technologies available in the market don’t directly contribute to revenue streams, which is why government intervention might be required for industrialists to use those. However, advocates say that ozonization is both environmentally-friendly and cost-effective. “The technology is good for the environment as the residual of the process is oxygen. The return on investment is three years and it is a one-time investment. It is the conventional treatment of wastewater that is costly,” the employee said.

It is important to note, however, that the environmental benefits of ozonization can only be realized if the process is properly handled for industrial use without human interaction. Compared to the gas we normally refer to as oxygen (O2), ozone (O3) is a reactive gas due to an extra atom of oxygen and therefore can have negative effects on living things.

SE Drop, Zaid’s company, proposes a different water recycling method called ‘Molecular Distortion Technique’. Their equipment, they claim, can clean over 90% of pollutants in used water, making it viable to be re-used for industrial use. This means that adopting this technology could halve the use of water in industry. The equipment can also be tailored for domestic use and grey water can be recycled to be subsequently used for washing and gardening, but not for drinking.

Currently, many factories and companies are simply disposing off their wastewater into the ground, and that eventually pollutes underground water which is then used by people living in close proximity for daily activities including drinking and cooking. In Karachi, untreated water makes it to the ocean, polluting it and harming sea life.

“If I live near an industrial complex and it is disposing off its water in the land, then the water coming from the bored well in my home will have a lot of chemicals that were released with the industrial wastewater and are unfit for human use. That is dangerous for health but unfortunately it has been happening,” Zaid says.

According to a United Nations report, consumption of contaminated water which leads to several waterborne diseases contributes to 40% of the deaths in Pakistan every year. Another report by the Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources (PCRWR), water scarcity and waterborne diseases are causing serious economic and health crises. After testing water samples from 25 major cities, they found that groundwater is increasingly becoming contaminated with bacteria and chemical pollutants. Mixing of untreated municipal and industrial effluents with surface and groundwater not only adversely affects aquatic life, but also freshwater resources, human health and agriculture.

“Despite repeated identifications by researchers and media reports, water quality remains below the desired level. A sampling examination conducted to test water quality in different locations across Karachi revealed that 97% of the samples were unfit for drinking. All these samples required appropriate treatment,” says Dr. Noman Ahmed.

According to last year’s Pakistan National Water Policy document, less than one percent of total wastewater in the country is treated before disposal. This refusal to use recycled water by industry is not only wreaking havoc by polluting underground water, it is also indirectly disturbing the geosphere.

Zahid Farooque, Joint Director of the Urban Resource Center (URC) in Karachi quoted a ten-year-old research that said that 50,000 tanker-trips take place in Karachi to supply water to industry every day. Apart from this, industry also gets line water. The research was conducted by Parween Rehman, a renowned social activist who was assassinated in 2013 for her intrepid criticism of mafias in Karachi and their political patrons.

“Drawing so much water from the ground certainly hurts the natural underground structure. The underground water level is falling,” says Farooque.

Dr. Noman corroborated Farooque’s assessment that drawing a lot of underground water weakens the ground and changes soil strata. It becomes difficult to raise buildings and increases construction expenses.

SE Drop’s co-founder and Zaid’s partner Usama Javed Shaikh believes that their startup possesses a viable solution that will incentivize industry to reduce their use of fresh water. “Almost all industries in Pakistan do not treat their wastewater before dumping it due to limited resources. Wastewater treatment plants require a very large area and are very costly. SE Drop’s plants are small and about 40% to 50% more economical than conventional wastewater treatment plants, which are called Effluent Treatment Plants (ETPs),” he says.

“We have developed a water-treatment plant that not only treats water that can be safely disposed off but can also recycle 70% of it for reuse, thereby taking account of both water scarcity and water pollution,” Shaikh says. “Thus, we are providing a single solution for two of Pakistan’s gravest issues: water scarcity and pollution. The technology we are using is versatile, in the sense that it can recycle all kinds of wastewater, be it sewage waste from individual homes, buildings, housing societies or industrial waste of any category.”

According to Dr. Noman, if industries start using recycled water, their demand for water would significantly reduce and the savings can be distributed among the areas that are most affected by water scarcity.

But it all trickles down to the whether or not the technology needed to reclaim water for industrial use is cost-effective or not, a problem that companies like SE Drop are trying to optimize for. Pakistan’s export-based industry, especially textile, has largely been known as a low-cost industry, which means that it gets international business on the basis of its low-cost operations. Industry sources that if costs increase, then Pakistani exporters are expected to lose business.

The government is always looking to boost exports, going to the length of offering tax rebates to export-based industries so that they can stay competitive. These industries earn important foreign exchange for the country, so they generally remain away from government scrutiny. But the subject of water needs to be taken seriously, both as a resource and public health issue.

“When piped water gets mixed with contaminants due to all these various reasons, public health hazards instantly emerge, as was found in Karachi’s neighborhood Landhi some years ago where hundreds of people were affected by gastroenteritis after using impure water,” says Dr. Noman Ahmed of NED. “The middle-income and upper-income groups either use bottled water or resort to filtration, ultraviolet treatment devices or just boil water for domestic use. But the poor possess neither the awareness nor the means to make water safe for consumption.”