Conventional wisdom dictates that automation, such as bank transfers for pensions and other government benefits, can help alleviate and might even solve the problem of fraudulent draws in the name of pensioners who are no longer alive or eligible. A new government scheme that has been in place for almost three years proves this assumption wrong.

In 2016, the Ministry of Finance decided that it would adopt a Direct Credit Scheme (DCS) to pay pensions for its full-time employees who retired as officers from Grade 17 through 22. Regular pension payments would be transferred directly into the pensioners’ accounts instead of them having to wait in long lines for hours with pension books and forms to get their monthly payments.

The procedure to convert to the DCS system of pension payments was simple although one had to follow several steps that could be time-consuming. First, eligible retirees had to collect their disbursement portion from the National Bank of Pakistan (NBP). To do so, they needed to acquire an authority letter from the office of the Accountant General of Pakistan (AGPR), which has branches in Islamabad, Lahore, Karachi, Peshawar, Quetta, and Gilgit. Then, the DCS form would be verified from the bank of the pensioner’s account.

The verified form and the disbursement portion was submitted along with the pension payment order to the AGPR office. An indemnity bond drawn on a Rs.20 stamp paper, against the verified form and attested by a notary public, was required to be provided to the pensioner’s bank. Finally, both of these documents were to be processed by the department of the pensioner’s service (PPO) and the pension is directly credited to the chosen bank of the pensioner.

“Legally, NBP is not the required banking institution for pensions,” an executive official at the bank told Profit on condition of anonymity as they were not permitted to speak to the media. “But, because the salaries of government employees are paid through NBP, pensioners are already familiar with the staff and the procedures of the bank so they prefer to continue with what they know,” the executive said.

In essence, this new system — the Direct Credit System of Pension Payments (DCS) — provided two benefits at the same time: convenience for pensioners and more control over the process for the government. However, there is a major part of Pakistani culture at play here — our deference towards the elderly and their convenience.

According to a director of NBP, speaking on condition of anonymity, before pension payments were directly transferred to the accounts, there was a much higher number of “ghost pensioners.”

“Older pensioners sometimes have family members accompany them to the bank to collect their pensions. Sometimes, when the bank staff is familiar with a pensioner and their family members, they would allow a member of the family to bring signed documents from the pensioner out of courtesy, instead of forcing the condition that pensioners themselves be present [to collect the payment],” he said.

“This led to a fraud of hundreds of thousands of rupees from the national exchequer as family members continued to withdraw pensions on behalf of retired officials even when they had passed away, using forged signatures and fake attestations.”

According to the officials of the NBP, when this new DCS system was implemented, it eliminated most, if not all, deceased or fake pensioners in one go. When the biometric verification system for accounts was implemented, it is likely that the remaining fake pensioner accounts would also have been removed. The actual data for this latter move is yet to be compiled and released by the State Bank. However, even this will not stop the creation of new fake pensioners.

The official informed that when the DCS system was put into place, approximately four to five hundred thousand pensioners never turned up to activate their accounts, according to the bank official, who were then written off as fake or deceased. But did this put an end to the problem? Unfortunately, no. With the modernization of pension payments system, the problem of fake has in fact not decreased. But before we discuss the menaces that still remain, let’s try to put some things in perspective.

How the Pension system works in Pakistan?

Pension can be defined as a periodical payment made by the government – local or federal – in consideration of past service rendered by a government servant. Pension can be for compensation, invalidity, or retirement – by choice or superannuating. In case of the death of a government servant, in service or retired, the remaining family members become legal recipients of a proportion of the pension, provided some conditions are met.

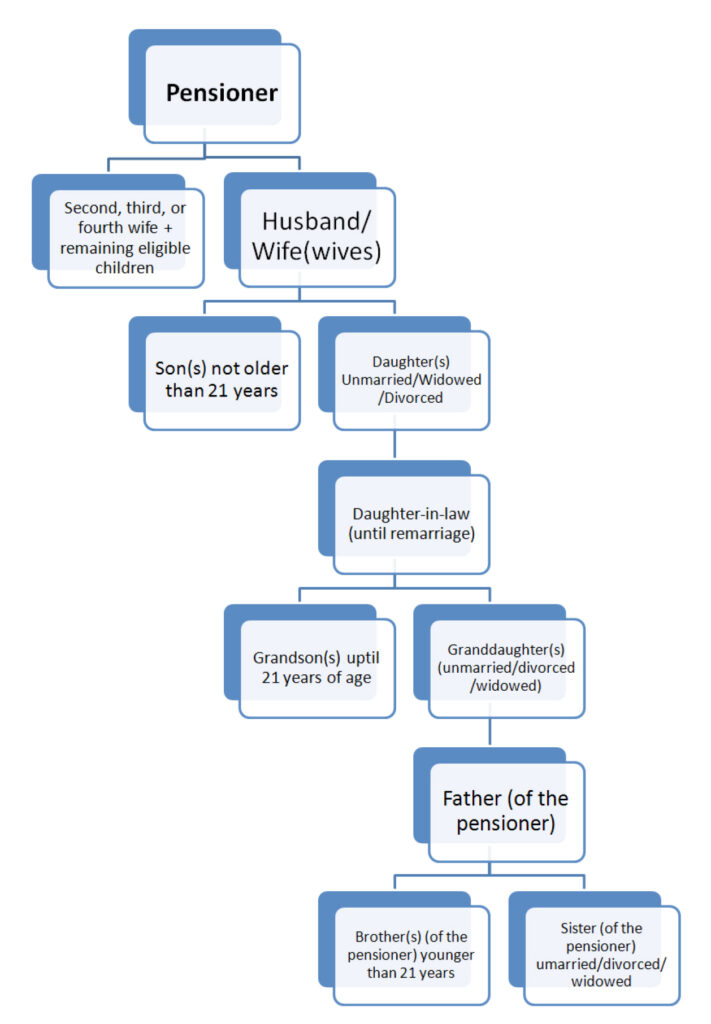

The first contender of the pension of the deceased government employee is the remaining spouse (husband or wife) or spouses (wives), who receive 75% of the total pension amount. In case a male officer had more than one wife, the pension amount is divided equally among the family members as long as there are less than four members in total. In case the family members are more than four, each widow gets one-fourth of the share of the pension amount and the remaining is divided among the eligible children equally. The eligibility for sons is less than 21 years of age. For daughters the conditions are being unmarried, divorced, or widowed, and up till they get married or remarried.

Daughter-in-law of a deceased officer can also receive pension payments, up to ten years, in case there are no surviving spouses or children of the pensioner. If there is a surviving grandson, and he is less than 21 years of age, or surviving grand-daughter as long as she is single. In case there is no above family member of the deceased pensioner, his or her father gets to receive the pension till death, in the absence of father as the contender, the brother of the deceased pensioner gets the pension until the age of 21, or unmarried, divorced or widowed sister. The brother and sister are legally eligible to receive such payments for up to ten years.

Monetising the scam

So how do we know what these 400,000-500,000 ghost pensioners could have meant for the national exchequer. First of all, like most other statistics in Pakistan, there is no official record of the exact amount of pensions paid or payable in a given month, or even a year. A call to the AGPR office will lead you to check with different departments that issue pensions and calls to those departments, such as post office, will bring you back to the AGPR office holding you in an endless loop of hoping between officials either refusing to share data or simply sending you someone else’s way – much like the blame game when it comes to their official responsibilities.

Therefore, we will try to estimate this amount from the data that is available publicly online. The federal government and the four provinces together had budgeted for Rs565 billion in 2017-18 for pension payments. The Federal government’s share from this stood at Rs342 billion, out of which the retired civilian employees of the federal government were to receive Rs82.22 billion in the current fiscal year. The current fiscal year saw the government announcing an increase of 10 percent in the pensions of all civil and armed forces pensioners of federal government, thereby giving an estimated amount of Rs90.44 billion for civilian pensioners.

As per a circular issued by the Finance Division on July 3, 2018, the minimum pension of a civil pensioner of the federal government was revised to a minimum of Rs 15,000. Since the pension fraud has been before this revaluation, to get a very conservative estimate for a possible ghost pensioner, we will take Rs 10,000 to be the average pension per month. Considering that the NBP official said at least 4 to 5 lac pensioners never showed up to transfer their pension to DCS system, the number for the payments per month to these pensioners (averaging 450,000 payments) will be (10,000 * 450,000) Rs 4.5 billion a month. The “hundreds of thousands of rupees fraud” then does not even come close. This pension fraud had been a thing going on since decades, but with these estimates even a single year’s loss equals Rs 54 billion.

There is another side to this story, that of family pension. Two-thirds of the pension of a deceased government officer is transferable to the remaining widow or widower, or divided among the surviving sons less than 21 years old, or unmarried, divorced or widowed daughters until their remarriage. What this means is that if a deceased officer does not have a remaining spouse, a son who is younger than 21, or a single daughter at home, the family will be better off not declaring the death of the parent. There are several ways this fraud had been committed, and while the ghost pensioners might have been wiped out by the DCS system, the remaining means are still up and running.

Loopholes remain

So, for example, NBP no longer allows joint accounts for pensioners, but ATM cards and debit cards are still issued for pension accounts. This means that anyone in possession of a card and its associated PIN number can continue to withdraw a pension payment.

There is a law that seeks to stop this sort of fraud: bi-annual submission of proof to the bank showing that the pensioner is alive and, in the case of widows, proof that a woman hasn’t re-married. However, like many laws, this one is not implemented very strictly either.

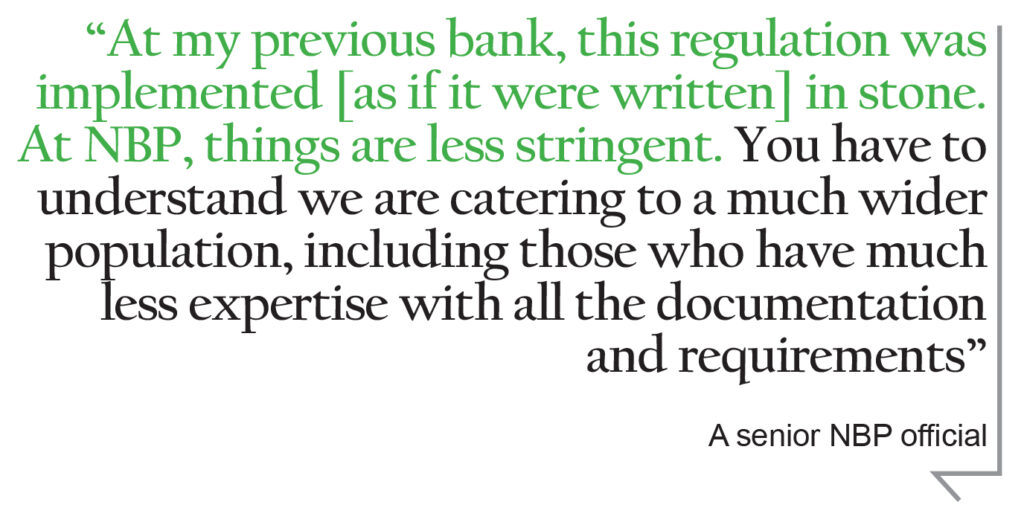

“At my previous bank, this regulation was implemented [as if it were written] in stone. If the account-holding pensioner did not submit a legal, attested certificate every six months, the account was blocked automatically,” says another senior NBP official who also worked at a senior position in a private, multinational bank, also on condition of anonymity for lack of authority to speak to the media. “At NBP, things are less stringent. But you have to understand that we are catering to a much wider population, including those who have much less expertise with all the documentation and requirements.”

But is it just sheer laziness and incompetence at NBP’s end or is it, as some people claim, a way to make extra money for some members of the NBP branch staff? A pensioner, who didn’t want to be identified claimed that he has heard of some bank staff asking for a monthly cut from families of deceased pensioners in exchange for relaxing the rules.

Then there is also no denying the fact that not only the process of transferring a deceased pensioner’s pension to his widow or children an extremely cumbersome task, but also that the amount is halved. There is obvious comfort and better money for the living remaining relatives of the pensioner to simply not declare their death.

But on the other hand are those who are committed to following the law, and they are the ones who keep the system running.

“I am here to submit the [required] documents, but I agree that many people do not care about these requirements,” said Ahmed Khan Niazi, a customer who was there to submit a death certificate for his recently-deceased father who had been a school principal and retired as a Grade-20 officer. “[These requirements] protect the bank’s customers as much as they protect the bank and the government’s money.”

The key point at this hour is to realize that DCS system has cleared fake pensioners and ghost accounts accumulated over decades. Biometric verification lend a helping hand to further the same cause. However, simply legislating is not going to put a permanent end to this fraudulent activity. There is still room, much smaller than before, but nevertheless still room for unlawful claims on pensions. The State Bank, and the National Bank in particular, would be remiss if they did not bring up a policy to nip this new nuisance in the bud before this one blossoms into another huge mess of ‘not-dead’ dead pensioners.

Good work

You are very right

Also suggest further steps to plug these loopholes

Are you sure about the tree diagram?

Comments are closed.