A report published by Small Arms Survey, a research project at the Geneva-based Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, in June 2018 estimated that civilians in 230 countries till year end 2017 owned 857 million firearms. What makes this number appalling is that it is 84.6% of the total number of guns in the world. Yes, militaries and law enforcement agencies do not own majority of the firearms, according to the survey.

Out of the over one billion firearms in the world, militaries hold 13.1% of the guns, which comes to 133 million, while law enforcement agencies hold a paltry 22.7 million guns, only 2.2%. The case of Pakistan is no different. The survey estimated that there were an estimated 43.9 million civilian-owned guns in Pakistan by the year end 2017, up from 18 million in 2007, much more than the estimates are for military-owned guns (2.3 million) and guns owned by law enforcement agencies (944,000), putting Pakistan at 4th spot for the highest civilian firearms holding, behind only the United States, India and China.

Forty-four million guns looks like a big business. A 9mm caliber pistol, which is the lowest caliber and the most demanded in Pakistan costs approximately Rs25,000 on the lower end of the price range. Of course, there are other, more expensive ones as well, depending on the manufacturer.

But given the fact that Rs25,000 is the cheapest a gun can get, that would mean that the total value of the 43.9 million guns in circulation in Pakistan is at least Rs1,098 billion, a highly conservative estimate.

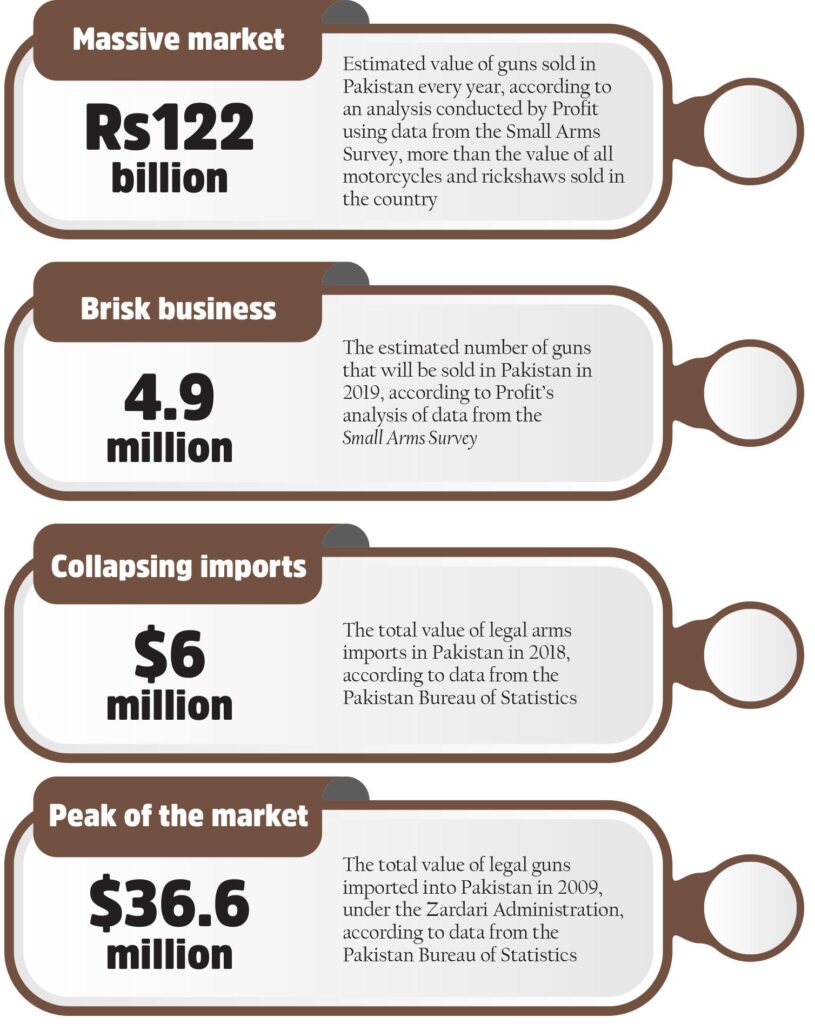

And the market has been growing at about 9.3% per year for the past decade, according to data from the Small Arms Survey. Extrapolating from that growth rate, the country will have 52.5 million guns by the end of this calendar year. And next year, another 4.9 million guns will enter the Pakistan market, meaning annual small arms sales in Pakistan are worth at least Rs122 billion ($764 million) and may well be worth more than $1 billion a year.

To put that in context, that is more than the value of all motorcycles and rickshaws sold in Pakistan in a year.

But walk into the shops of firearms retailers in Lahore and you would find no customers and empty inventory. Dealers say that it has been six years of misery in their business. The downfall of their business began when the Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PML-N), led by Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif took office in 2013. The anti-gun policies of the Nawaz Administration at the federal level, and the Shahbaz Administration in Punjab, curtailed arms imports, and banned licenses, all in a bid to regulate the industry in a country with several armed insurgencies and a high violent crime rate.

That, however, meant hard times for legal arms dealers.

“Our business is down since Mian [Nawaz Sharif] sahib’s government. He had an anti-gun policy. We expected that this government would do something about it, but I don’t blame them because they have bigger problems to look after. The items we deal in are not their priority. It is not a necessity of life,” says owner of Bukhsh Elahi and Co, a Lahore-based arms dealership.

The legal guns business has degenerated completely. On the supply side, imports have been disallowed, on the demand side, licenses are not being issued: there has been a blanket ban on issuance of arms licenses in Punjab. The District Commissioner’s Office in Lahore told Profit that the ban has been in effect since 2015. Dealers claim that the ban is not in effect in other provinces.

“There was a lot of demand earlier. From November till the end of February or March is hunting season and we had good sales in that period. People ask for cartridges, shotguns, rifles. Other customers would need it for self-defense or sporting, for competitions. Right now, we might get 15 customers in a day. Out of them only eight would have a license, and seven would not because licenses are banned. And of the eight that would have a license, only two would be potential buyers but then we have no weapons or ammunition because imports are banned,” says Syed Yasir Hassan, a Lahore-based importer of arms and ammunition and owner of Arsenal, an arms dealership.

Meanwhile, arms dealers argue that the regulations have done nothing to curb the widespread of use and ownership of guns, just made it more difficult to do so legally. They point out that the number of guns in Pakistan continues to rise rapidly, and of the 44 million guns estimated to be in the country in 2017, only 6 million were legally registered, with the rest in the black market.

Legal imports of arms and ammunition were only $8.24 million in 2007, according to data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, and peaked to $36.63 million in 2009 when Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), led by President Asif Ali Zardari, was in office. That was the heyday of the business, dealers say.

When the Nawaz Administration took office in 2013, imports were at $16 million and had decreased to $6 million by 2018, when the PML-N government, during its last days in office, lifted the ban on imports of arms and ammunition. Importers, however, say that though the ban has been lifted, the Ministry of Commerce is not issuing licenses, which is a prerequisite for imports.

“Only an SRO [Statutory Regulatory Order] was issued allowing imports but actual licenses were not issued. Old licenses expired when the old policy was changed. We are registered as importers but our actual document, which used to get renewed each year, we don’t have that. It’s like all other licenses that get renewed. We don’t have the required documents so we can’t show anything to the manufacturers about the imports permission,” says Yasir.

On the other hand, commerce ministry officials insist that the imports have been allowed after the SRO was issued by the previous administration at the end of its tenure.

Gun dealers argue that the process of doing a legal trade in guns is being made too onerous, which does not serve the government’s policy objectives of greater transparency into the gun market.

“Overall in Pakistan, laws related to guns are so strict, it is not even possible to do the trade otherwise. No arms importer in Pakistan is allowed to import automatic guns in the country. If somebody has been able to bring them in the country, he might have used forged documents or misdeclared the weapons, which is a criminal offence. All the Klashinkovs and automatic weapons can only be smuggled into Pakistan. Legal trade is not involved in that. That is all illegal trade. If you want to stem that, secure the border,” says Yasir.

“The procedure is that whenever a consignment comes to Pakistan legally, it will have a packing list with a record of all the weapons with their serial numbers, make, model, country of origin and all other details written on it,” he adds.

The data is entered into the database of customs authorities that a certain importer imported specific guns, from a specific manufacturer based in a specific country, with all the serial numbers.

“We get possession of the consignment only when we clear all the taxes,” Yasir says. “For as long as the consignment is there and not cleared, you have to pay demurrage on it,” he adds.

Demurrage is the tax/fine an importer pays to the customs authorities if his consignment is not cleared on time. It is charged on a daily basis and is higher for arms and ammunition because gunpowder is flammable and carries a high risk if kept with other items.

As per the old policy, importers were authorised value-based licenses. They could only import a certain number of weapons based on the monetary value of their license, which differed for each importer. For instance, an importer might be allowed a quota of Rs2 million imports for a year, while another importer might have a license of Rs4 million worth of imports. An importer could import a certain number of weapons equivalent to the value of their license. That flooded the markets with Chinese and Turkish made guns and ammunition because they were less expensive and would allow more units against the more expensive ones such as the US, European or Brazilian made weapons, which are more expensive and hence a smaller number of units could be imported.

The value-based licenses gave rise to a legitimate problem of under-invoicing. Where a gun would cost $200, importer would declare its price to the customs authorities to be $80, which would be a loss to the government revenue, even though customs authorities would clear the consignment at a higher price than declared, according to their own estimates of the prices of weapons.

At times, these consignments would be confiscated and would stay with the customs authorities, and importers would be required to pay demurrages for each day it would stay with the authorities, which would become losses for importers. And the best the government could come up with was to abolish the import regime.

Killing the legal demand

Arms dealers point out that encouraging the legal trade will help the government more effectively regulate gun ownership in the country.

Here is what it takes when somebody wants to purchase a weapon. First, they will have to apply for a license with provincial home department or the federal interior ministry, depending on where they live. The licence takes anywhere been six weeks and two months to get. The licences are all linked to a government database that monitors legal weapons ownership.

Only once licenced can a person buy a gun. But the process does not end there.

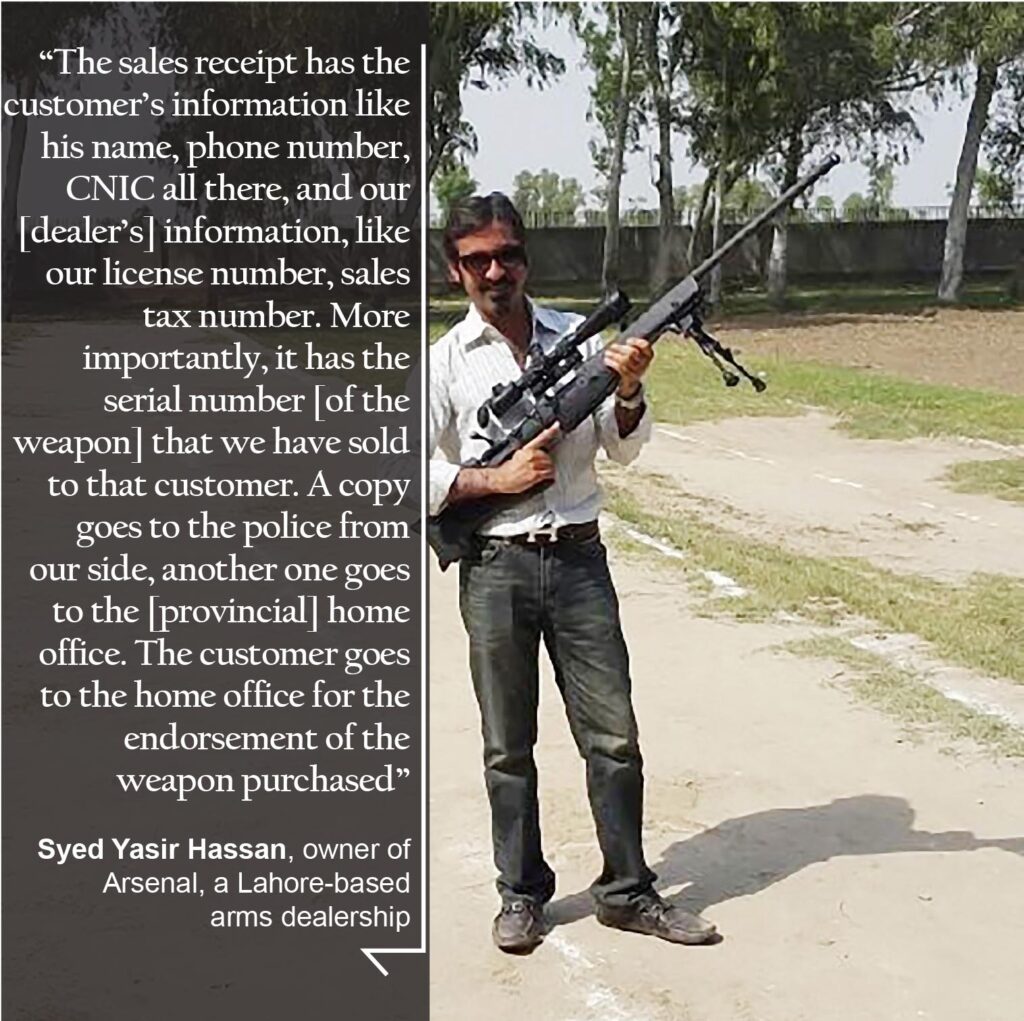

“The sales receipt has the customer’s information like his name, phone number, CNIC all there, and our [dealer’s] information, like our license number, sales tax number. More importantly, it has the serial number [of the weapon] that we have sold to that customer. A copy goes to the police from our side, another one goes to the [provincial] home office. The customer goes to the home office for the endorsement of the weapon purchased,” Yasir says.

“If the police or any other department wants to check, they will have the complete list of all the weapons imported by us and will be able to tally it with our receipts that which weapons have been sold. If they check our stock, they will be able to verify so there cannot be anything fishy in all this. Only if a weapon is missing, they will know that there is something wrong,” he says.

But the legal trade is struggling with regulations and formal licenses are banned, all while reports continue to surface of government officials illegally issuing backdated or otherwise unauthorised licenses in exchange for hefty bribes. The home department recently unearthed a scandal of officials in the Lahore District Commissioner’s Office hundreds of fake, forged and illegal arms licences, involving millions of rupees in bribes. Other district offices were also found involved in the scam and the probe has only been widened.

“When you stop something legal, the illegal will start. They don’t give licenses anymore, which can still be received through DC Office illegally. There are lots of scandals involving that. You have to start giving licenses legally. Nobody in this space wants to keep illegal weapons but people have no other way other than obtaining it illegally. So, because of that, those outlets which are taxpayers and want to do this legally, they are suffering, but the illegal ones are thriving,” say Bukhsh Elahi and Co.

All this comes at a time of macroeconomic slowdown in the country. “The demand for weapons has decreased in the last 5 years, especially since the devaluation of the rupee against the dollar,” says Muhammad Salahuddin, a Lahore-based importer of arms and ammunition

What makes the process of obtaining guns more cumbersome, says Yasir, is that even if somebody has a license, they will need another letter from Home Office giving them permission to purchase the weapon.

“The policy can be a lot better. They could have had computerised booklets just like passports. Whenever you have to change your weapon now, get a new or a used one, you have to get a new license which takes 1.5-2 months. And then you need permission again to buy it,” he says.

Profit has learnt that the Punjab Home Department is mulling lifting the license ban for those individuals who are tax-filers. When contacted, the Home Department refused to comment on the development.

No

No history man

Comments are closed.