Hanaa Lakhani’s professional career path is the kind that would give the average Pakistani parent some anxiety. Around this time two years ago, the twenty-something was an operations analyst at the investment bank JPMorgan in New York. Today, she is the chief marketing officer for a tiny startup tucked away in Bahadurabad, Karachi. A bit of a change, to say the least.

The driving force (haha) [Editor’s note: laughing at your own bad puns is just sad] behind this career upheaval is the ride-sharing startup Roshni Rides. The project is the brain-child of four founders: Hanaa Lakhani, Gia Farooqi, Hasan Usmani, and Moneeb Mian.

All have backgrounds similar to Hanaa’s: all four are of Pakistani origin but were born and raised in New Jersey, attended Rutgers Business School, and then in 2018, packed their bags and moved to Karachi – with $1 million in prize money in hand to jump start their company.

Roshni Rides is unique for many reasons. For one, its entrance in the Pakistani market appears to be at the right time. Uber and Careem have already familiarised many Pakistanis at least with the concept of ride-sharing. Airlift and Swvl, brand new companies announced In Pakistan with much fanfare this year, are providing bus and shuttle services. Roshni has slowly but steadily grown in the two years since 2018, and has found its niche as an alternative to van wallas for women.

But that’s not why you should pay attention to Roshni. What makes the startup compelling, is that fundamentally, this is a story of how a bunch of American college kids decided they could pull this off in a country they have never lived in before.

It is a story of how to approach a very Pakistani market with very can-do American spirit. At the most recent 021Disrupt conference, Rabeel Warraich, founder of Sarmayacaar, coined a term for people like this: “Waapistanis.” Roshni Rides is the perfect example of that diaspora trend.

The competition that started it all

Hanaa met her cofounders while studying at Rutgers Business School as an undergrad. The four were all majoring in supply chain management, so often saw each other in the same classes. Plus, they were all Pakistani-American, and Muslim.

“Just being in America and spotting another Hijabi or Muslim in your class group, you just automatically gravitate towards that,” says Hanaa. “‘I look like you’ – that’s how our initial friendship really began. I grew up in a predominantly all-white neighbourhood, with a majority Jewish and Christian community. I really wanted to go to Rutgers because it was a place where I could be friends with other Muslims.”

In her junior year at Rutgers, the group of friends decided to compete in a case-study competition. These were fairly common at business school, and involved companies coming to campus and posing problems for students to solve. Their first competition was for the American transportation company C.H. Robinson. Their group won first place out of 15 other groups. Their prize? $50. “That was really exciting for us as college students,” Hanaa recalls.

And that was just the start. The next year, they won a campus-wide competition, this time working on an e-commerce solution for the American chain store Target, cementing their friendship and strong work relationship.

After graduation, Hanaa, who was a year ahead of her friends, went off to work at JPMorgan, the largest financial institution in the world by assets, as an operations analyst. But in her own words, despite it being the “typical glamourous job” that any business student would want, she found the work unfulfilling.

That is when Hanaa discovered the Hult Prize competition, an annual competition for new for-profit companies that want to make a social impact. Over 250,000 students across campuses compete with one another pitching different social enterprises. Fortunately, one of the competition’s loopholes was that there could be one member on the team who was a non-student.

This was Hanaa’s out. She called up her old friends at Rutgers and convinced them to apply, and the four began researching on their concept in October 2016, or Version 1. The four had come up with a plan for a bicycle sharing platform for refugees settlements in Jordan. The proposal was modelled after the bicycle sharing company Citi Bikes, based in New York.

Version 1 helped them win the campus round in December 2016. But afterwards, a judge helpfully pointed out: “You guys are creating a business for refugees camps in Jordan, but all four of you are Pakistani-American and have never been to Jordan. You don’t even speak Arabic, so how are you going to make this business a reality?”

Good point. The group then decided to do something in the country their parents had migrated from. That led to Version 2, a solar-powered rickshaw shuttle service in Orangi Town, Karachi. Version 2 helped them win the regional competition in March 2017. In May and June of that year, the group flew out to Orangi Town to conduct a pilot project.

To fund it, they leaned into their Pakistani and Muslim communties, and actually managed to raise $30,000 through LaunchGood, a sort of Muslim-focused GoFundMe. The team rented an office space, bought three solar-powered rickshaws, and waited…

It turns out there was just one problem: nobody in Orangi Town cared about the solar panels. “People are not going to pay extra something just because it looks glamorous. That two month study involved a lot of learning,” say Hanaa.

So they decided to drop the solar idea, as environmentally friendly as it was, and go for Version 3: a rickshaw pick and drop service. After attending an accelerator program between between July and August 2017, they pitched their idea in the final round at the UN headquarters in September 2017. Version 3 helped them win the Hult Prize, and $1 million.

“It was kind of a mixture of emotions, like wow I have never received this many text messages in my whole entire life. There are so many Muslims in our area that were rooting for us and watching the pitch live. We’ve always had support from our Rutgers Muslim community, and our local mosques in New Jersey.” says Hanaa.

In January 2018, the team packed up their belongings in New Jersey and headed to Karachi – permanently.

Roshni Rides today

So what does Roshni Rides look like today? Well, as soon as the team arrived, they switched over to Version 4, a pick and drop service for working women. As Hanaa puts it, “We realized people don’t want to stay in their settlements. The real opportunity and the real money is in the main city of Karachi.”

Version 4 is basically a B2B service that connects corporations with a large female workforce to use Roshni Rides for daily use. Roshni received their first client in July 2018. Today, its clients include Daraz, HBL and Aman Foundation.

At the same time, because of their renewed focus on women, and how women use cars and call transport in Karachi, they decided to simultaneously launch Version 5 in September 2019: a carpool service for individual women and school children. “We wanted to reach out to vulnerable communities that don’t really have great solutions out there for them.” says Hanaa.

Despite all of these variations within the last two years, Hanaa still reacts at the mention ‘pivot’. “Pivot implies that you do not know what you were doing. We’re instead redefining. We’ve always wanted to be a company that listens to our customers’ wants, rather than just pushing a solution.”

Today, Roshni Rides operates out of a bright orange coloured office to match its logo. The office is a bustling space with around 30 people employed, including the four founders. Gia Farooqi is the CEO, Hasan Usmani, the COO, and Moneeb Mian is the CFO.

The startup employs around 160 drivers that complete around 20,000 rides a month. Most of the cars are hatchbacks, that pick and drop two to three women per ride. Most of their customers are women who live in North Nazimbad, Gulshan-e-Iqbal and Gulistan-e-Jauhar, i.e. areas in the north of Karachi, who travel every day for work to Korangi, Clifton, and Defence in the south of the city.

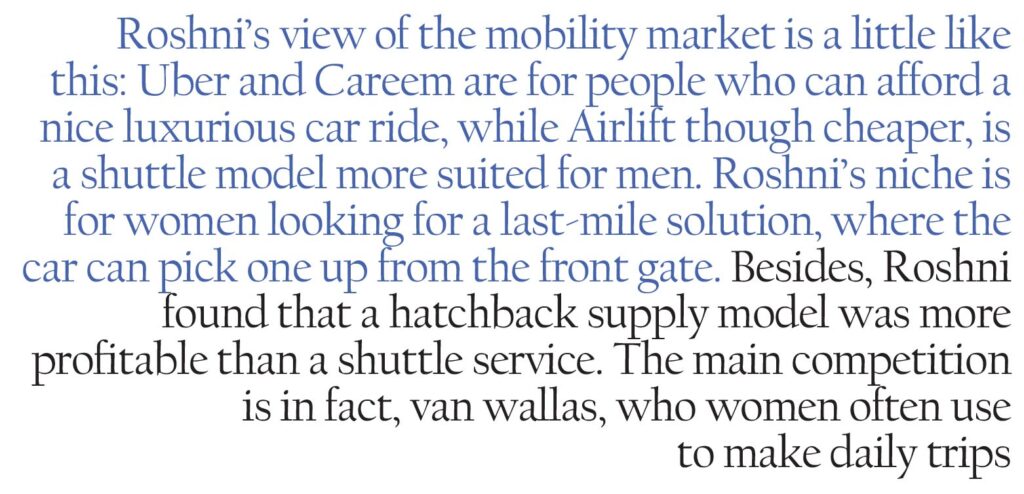

Roshni’s view of the mobility market is a little like this: Uber and Careem are for people who can afford a nice luxurious car ride, while Airlift though cheaper, is a shuttle model more suited for men. Roshni’s niche is for women looking for a last-mile solution, where the car can pick one up from the front gate. Besides, Roshni found that a hatchback supply model was more profitable than a shuttle service. The main competition is in fact, van wallas, who women often use to make daily trips.

Roshni prides itself on two aspects. For one, it is incredibly proud of its vetting process for drivers. “We would be nothing without the drivers we have, they make up our Roshni family that we have here.” says Hanaa.

The company’s four step vetting process involves multiple security checks and in-person interviews. “If you have a bad driver, really out of necessity, women just deal with it.” Roshni is aiming to change this, by partnering with Care Foundation in Pakistan to provide training for drivers on how to talk to customers, particularly women.

Secondly, Roshni prides itself on being quite lean financially. Along with revenue earned from the rides, the $1 million won in 2017 has been financing this entire operation for the last two years. About 75% of that initial seed money has been used up, according to Hasan Usmani, the COO. Roshni also does partnerships with different brands, including in vehicle advertisements.

I was introduced to the concept of an ‘experience basket’, or a bag of goodies that each Roshni Ride has. “People are stuck in cars from anywhere to half an hour to an hour every day – why not think about things that they want if they’re stuck in traffic?” says Hanaa.

Roshni has partnered with large brands like Unilever, who stock samples of their shampoo in the basket, to much more obscure local brands like Primary Skincare (a cult toner and face mist famous on Instagram).

But in the future, how is Roshni going to grow without extra investment? Just this October, companies like Airlift, a shuttle service raised $12 million, and Egyptian bus company Swvl announced a $25 million investment in Pakistan. Where are Roshni’s millions?

While ever polite, Hanaa is practically dismissive of that kind of fundraising, calling it ‘celebrity play’. “Swvl and Airlift are burning hundreds and thousands of rupees on simply just running cars around; empty by the way, all of them are empty. We know how much they are burning…literally just for brand presence.” Instead she dubs Roshni’s lean approach a ‘responsibility’ on the founders part, or an ‘amanat’.

It is easy to criticize Airlift for wasting rupees, but at least one still sees Airlift buses all over Karachi, whereas Roshni still does not have that kind of brand presence.

But that is fine for Hanaa. She says Roshni is focused on developing their product and app first, pointing out Airlift’s technology is quite glitchy and their tracking capability does not work.

Still, Hanaa wants to make it clear: she is not against competitors, in fact, she welcomes the growth and competition in the mobility market. “We actually really enjoy other solutions out there – at the end of the day there’s over 22 million people that live in Karachi, not one solution is going to be able to fix it.”

“We’re focused on unit economics, and sustainability. If we are able to make X amount of women’s lives easier, and make their commute dignified, then that’s what we’re going to do.” she says.

The American Twist

A small digression: this reporter herself is 25 years old. I mention this because one of the first things you notice is how young everyone in the office is. No, seriously young. Take Hasan, who met me wearing slides, sweatpants, a Marvel shirt and a backwards baseball cap.

As per Hasan, being young has its advantages and disadvantages. “The advantages are that we’re hungry, we’re passionate. We’re willing to put in the work and effort that’s required to do whatever we’re going to do. The cons are obvious, that we don’t have as much experience.”

But despite everyone’s relative youth, it is still striking how professional everyone is. It’s a very specific, very American, kind of corporate talk, from the poised, carefully constructed answers that Hanaa gives, to the sort of blunt confidence that the other founders exhibit.

Hanaa chalks out that kind of attitude to their experience in business school. “Literally in our business school classes we were taught how to formally write emails, how to dress, how to even give a handshake. There all cues of being a professional: eye contact, smiling, body language, etc.”

“Coming here as a professional end was a bit of a struggle because Karachi is a bit more lax – not as lax as other cities in Pakistan, but for us, lax. And there’s this culture here of ‘Inshallah it’ll happen, ho jayega, ho jayega, but things don’t actually end up happening.”

Hasan echoes that sentiment, noticing that despite his young age, he has been put in the uncomfortable role of micromanaging a lot of his juniors.

“We want to create more, let’s say, an autonomous work culture” Specifically he wants to create that startup culture of ‘exploration’, of being comfortable with failures. It is easy to see why he thinks that: the 24 year old moved across continents to set up a ride-sharing app with little support, and a mild language barrier. Of course he is comfortable with failure; but try instilling that in Pakistan.

Being American comes with another set of challenges ie navigating the state of Pakistan. For one, none of the founders were expecting the amount of red tape found.

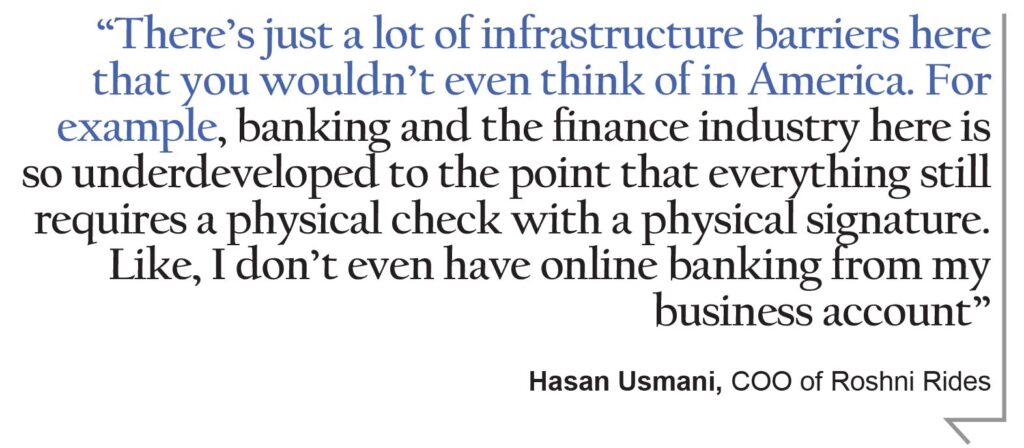

Says Hasan: “There’s just a lot of infrastructure barriers here that you wouldn’t even think of in America. For example, banking and the finance industry here is so underdeveloped to the point that everything still requires a physical check with a physical signature. Like, I don’t even have online banking from my business account.” Hanaa said setting up a bank account took three months in Karachi – a process that would have taken less than an hour in New Jersey.

Then, there is a Karachi-specific problem: the founders had never encountered mafias before. During their pilot project in Orangi, the team struggled to get permits from the government, all the while trying to hope their rickshaws were not going to be burnt down by the transportation or water mafia.

“That’s a huge learning lesson, especially for us coming from places like America where mafias and stuff like that just aren’t a concept,” says Hanaa. Maybe not quite true. The Sopranos may be fiction, but it had basis in reality. And the notorious mobster John Gotti was based just across the river in New York.

Looking to the future

While Hanaa may talk about Roshnis’s amanat to be lean, the truth is, the company is looking to grow. As per Hasan: “We want pick and drop or carpooling to be synonymous with Roshni. If there’s any woman that wants a pick and drop, the first thing that’s going to come to her mind is Roshni.” He estimates the company is about 20% close to achieving that goal.

With improvement in their model and technology, Roshni might even be ready for mass scale. Their next steps are still to look for investors, to raise money at least greater than $1 million.

It should not be a problem. After all, as Hanaa says very matter-of-factly, since their undergraduate days, “we’ve always been great at pitching”.

Good comapny but with a reckless and badasss customer service,. had a bad experience already and not willing to recommend

Comments are closed.