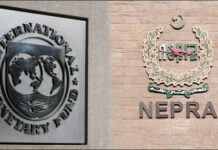

Perhaps the single biggest promise that Nawaz Sharif made when he ran for prime minister in 2013 was fixing Pakistan’s chronic energy crisis. That has been his single biggest obsession since the day he took office as prime minister, and his critics would argue, the genesis of some of his biggest mistakes in policymaking.

Unlike education, healthcare, taxation, and other critical areas, energy is one where both the PTI and PML-N believe they have strong subject matter experts in senior leadership positions within the hierarchy, and both sides have very different views on how best to manage the Pakistani energy sector. Nonetheless, there is an agreed baseline of facts that cannot be argued with, and we lay them out below.

We begin with the following premise: if everyone in Pakistan paid their electricity bills in full and on time, there would be absolutely no load-shedding in the county, ever. Load-shedding, in other words, is the consequence purely of two governance failures on the part of all power companies in the country: a failure to prevent theft of electricity from the power lines, and a failure to collect 100% of the bills that are issued to customers who are not stealing it directly from the grid.

The fact that these failures are currently happening is the reason behind circular debt, and circular debt is the reason Pakistan does not have enough power plants, and the ones it does have are producing at less than optimal capacity.

Here is how this works.

Electricity tariffs in Pakistan are determined by the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA), which determines which costs each power company is allowed to charge for its calculation of revenues and costs, which in turn feed into the calculation of what tariff it is allowed to charge its customers. Now, NEPRA is aware that it is operating in Pakistan and so for power distribution companies (LESCO, K-Electric, etc), it allows them to include the cost of theft – which is given the cleaner euphemistic name of “transmission and distribution losses” – as part of their cost structure.

This is where things start to go wrong.

Where circular debt comes from

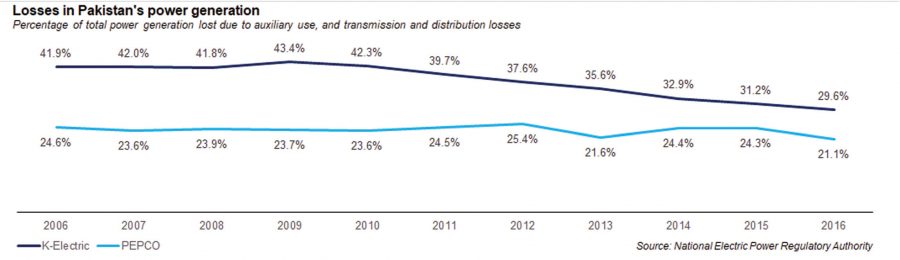

Transmission and distribution (T&D) losses can occur for technical reasons as well (ask your local physics teacher about resistance in wires), and in more advanced economies, can reach as much as 7% of the total electricity generated. In Pakistan, NEPRA estimates that total T&D losses came to 21.1% among the government-owned companies (which most analysts believe is understated) in 2016, and 29.6% in the privately-owned K-Electric during that same period.

The problem: NEPRA only permits these companies to include T&D losses of up to 15% in their allowed cost structure. And it allows absolutely zero losses for failure to collect bills, a number that averages about 12% nationwide during that same period.

So, all told, about 33% or so of the electricity produced in Pakistan is either lost in transmission, stolen, or billed but not paid for. And NEPRA only allows power companies to deduct 15% of it from their costs, which still leaves about 17% of which to account for.

And that, dear reader, is where circular debt comes from.

Where power distribution companies cannot recover the cost of theft, they cannot pay the full amount they own the power transmission company, which in turn then cannot pay its full bills to the power generation company, which then cannot pay their fuel suppliers, who in turn end up having trouble paying the international oil companies from whom they buy the oil.

Every few years, the government decides to “clear” the circular debt, which effectively means converting the amount lost due to uncollected bills and theft into a government subsidy that is then paid out.

Why, any logical person might ask, then not simply just have NEPRA allow higher allowances for electricity theft in the first place? There are two reasons, the first of which is that it would be unfair to the customers who pay their bills in full and on time, and the second is that the lower limit is meant to be an incentive for the power companies to curb their losses. That sounds fine in theory, but as you can see from the chart of line losses, the state-owned power companies managed by Pakistan Electric Power Company (PEPCO) have basically seen no real change in their line losses over the past decade.

By the way, this amount is over and above the subsidies that the government pays to power companies, which is another matter entirely and one worthy of discussion in its own right. The short summary of the power subsidies discussion is this: in theory it is meant to help make electricity an affordable right, but in practice, according to a study by the World Bank, about 90% of electricity subsidies go towards lowering the bills of the upper middle class who can afford to pay full price for their electricity.

And all of this is before we have even been able to get to the fact that the government has recently committed to building massive coal-fired power plants all over the country at the exact moment when the effects of climate change are beginning to badly affect Pakistan, and solar power has now become economically competitive with other sources of electricity.

……………………………….

The debate

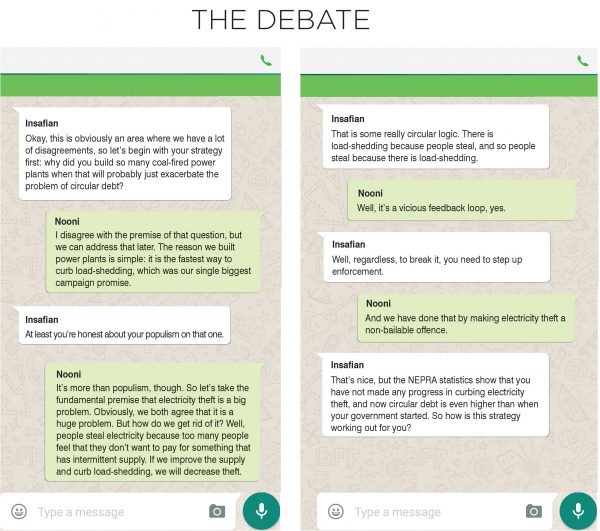

Insafian: Okay, this is obviously an area where we have a lot of disagreements, so let’s begin with your strategy first: why did you build so many coal-fired power plants when that will probably just exacerbate the problem of circular debt?

Nooni: I disagree with the premise of that question, but we can address that later. The reason we built power plants is simple: it is the fastest way to curb load-shedding, which was our single biggest campaign promise.

Insafian: At least you’re honest about your populism on that one.

Nooni: It’s more than populism, though. So let’s take the fundamental premise that electricity theft is a big problem. Obviously, we both agree that it is a huge problem. But how do we get rid of it? Well, people steal electricity because too many people feel that they don’t want to pay for something that has intermittent supply. If we improve the supply and curb load-shedding, we will decrease theft.

Insafian: That is some really circular logic. There is load-shedding because people steal, and so people steal because there is load-shedding.

Nooni: Well, it’s a vicious feedback loop, yes.

Insafian: Well, regardless, to break it, you need to step up enforcement.

Nooni: And we have done that by making electricity theft a non-bailable offence.

Insafian: That’s nice, but the NEPRA statistics show that you have not made any progress in curbing electricity theft, and now circular debt is even higher than when your government started. So how is this strategy working out for you?

Nooni: It needs more time to fully start showing results. Culture changes do not take place overnight, but I’m glad you brought up the NEPRA statistics, because they show something else that I want to bring to your attention too: notice how the state-owned companies have no improvement in line losses, but the privately owned K-Electric has shown marked improvement. So why are you against privatisation if you agree that line losses need to be curbed?

Insafian: First of all, I am not against privatisation. I just don’t think it is the panacea for all ills that you seem to think it is.

Nooni: That’s a gross mischaracterization of my views, but stop ignoring the question: why do you oppose privatisation of the electricity distribution companies?

Insafian: Again, I am not opposed to any privatization per se, I just think it should be accompanied by a strategy.

Nooni: Okay, so what strategy do you have here then?

Insafian: Well, it’s a very simple premise: the government should privatise power generation companies because that is where the private sector’s technical expertise can help turn around those ailing companies. But the problem at the distribution companies is not one of technical expertise. It is one of law enforcement, which is a function that even you, in your free market zeal, would agree belongs in the hands of the government.

Nooni: Cheap shot at the belief in free markets, but to rebut your claim: there is technical expertise involved in reducing line losses and K-Electric’s success is proof.

Insafian: K-Electric inherited a system so bad that they were obviously going to be able to overcome at least part of the problem with technical solutions. They are now running into the problem that cannot be solved without law enforcement help, and that is why their progress has slowed in the last couple of years.

Nooni: Fair enough, though one other big factor that probably helped them was the ability to shift the burden of load-shedding away from areas with low theft and towards those with high theft. The courts have prevented us from adopting a similar strategy in the PEPCO-owned DISCOs.

Insafian: So you believe in collective punishment?

Nooni: Absolutely not, which is why I don’t want law-abiding, bill-paying customers to be punished with load shedding if we can help it.

Insafian: What about those people in high theft areas who are also paying their bills? Why are they being punished for the sins of their neighbours?

Nooni: Looks, it’s obviously not an ideal solution, but a problem as large and complex as rampant electricity theft does not lend itself to elegant solutions. This is an approach that shows results, and shows them in Pakistan, so why not try it?

Insafian: Because it is not really a fair one. The low theft areas are richer, the high theft areas tend to be poorer. You’re punishing the honest poor for being poor while exempting the rich thief from any punishment because of the circumstances of their birth.

Nooni: Again, I’m not arguing that it’s the most egalitarian way to achieve results, just that it is a faster way to at least narrow the scope of the problem before we get around to tackling the law and order problem at the heart of all of this. And in a country with as many problems as ours, sometimes “good enough” will have to do.