If one had to reduce the state of an entire nation’s healthcare to a single number, it would be average life expectancy, particularly how that has changed over time. For Pakistan, that number stood at 49.3 years in 1964, and has since risen to 66.4 in 2015. The average Pakistani, in other words, lives 17.1 years longer than they did half a century ago. That sounds impressive, until you realise that during that same time, the average Indian saw their life expectancy go up by 23.3 years, from 45.1 years to 68.4 years.

How did that happen? How did India leave Pakistan behind in its dust when it comes to the healthcare of its citizens?

Quite simply: they spent more money.

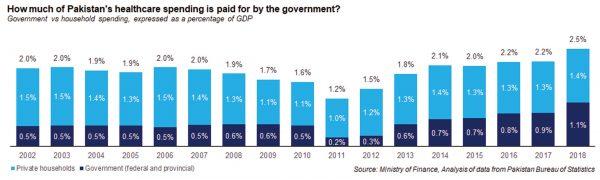

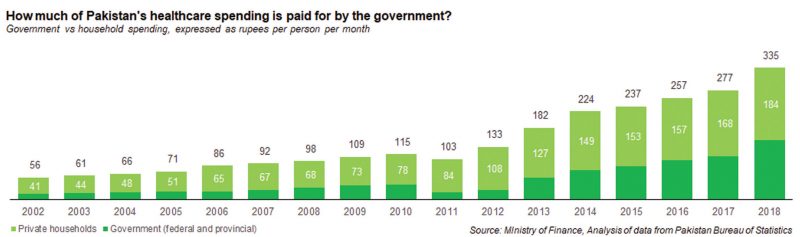

Healthcare, until recently, has not been a priority of any government in Pakistan. If anything, judging by the high degree of volatility seen in the budget numbers, healthcare seems to be the place that governments have previously sought to extract spending cuts from in their desperate bid to balance the budget.

As recently as 2011, the government of Pakistan spent only 0.2% of total GDP on healthcare. That number has since then risen sharply to 1.1% of GDP, an increase driven almost entirely by larger provincial allocations towards healthcare spending (and a testament to the genius of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution and the 7th National Finance Commission Award, which moved spending authority towards the provinces).

Add in private household spending on healthcare, which has hovered between 1.0% and 1.4% of GDP in any given year over the past two decades, and one gets total healthcare spending numbers that sound slightly more respectable. The year 2018 is expected to see Pakistan’s highest investment yet in the healthcare of its people: at 2.5% of GDP, of which 1.4% is expected to come from private spending.

How does that compare? Well, in 2010, when all of Pakistan collectively spent about 1.6% of our GDP on healthcare, India spend 5.6%. And the results are obvious.

The reasons as to why healthcare should matter to the economy – besides generally being a very large component of broader human welfare of a country – are obvious: healthier families and workers result in higher productivity, which boosts both household incomes and overall economic productivity.

So why have we so thoroughly neglected to pay any attention to healthcare then?

Well, it did not help that for much of our history, healthcare was stuck as part of the federal budget, where it had to compete with interest on the national debt, defence spending, and other, flashier avenues of spending, such as transportation or energy infrastructure. Once this area was moved out from there, and towards provinces that were controlled by competing political parties, healthcare became a priority, and the allocations of money began in earnest (it is too soon to have a full measure for what outcomes that will bring). Since 2011, government spending on healthcare has risen by an astonishing average of 33.9% per year.

What that spending has achieved is to make healthcare more accessible than it has ever been in Pakistani history. The total number of doctors and nurses in Pakistan hit a record high this year, which is not surprising in a country with a rapidly growing population, but what is more encouraging is that the number of doctors per capita has also hit a record high. In 2017, there was doctor for every 957 people, compared to one doctor for every 1,162 people in 2011.

The number of hospitals – and the number of available beds in those hospitals – is also rising at a steady clip. In 2017, there was one hospital bed for every 1,580 people, which is up from one bed per 1,647 people in 2011.

What happens next to the healthcare sector will have a significant impact on Pakistan and its economy for decades to come, which is why the policy debate surrounding healthcare is of utmost importance.

On the policy front, it appears that most provinces are engaged in policy initiatives similar to those in education: improving the physical infrastructure first and worrying about the surrounding conversation around designing a healthcare system later.

Nonetheless, given how large a healthcare system can be, and how rapidly its costs can start to escalate, it is important to start having those conversations about designing the system now, before Pakistan ends up stumbling into a system that it later finds it can ill afford, but upon which millions of people will be dependent by then.

For one thing, Pakistan’s healthcare system seems to have a heavy emphasis on hospitals, which is the most expensive setting of care. While all provincial governments are seeking to build out clinics and other primary care facilities, these tend to get less attention – and less money – than hospitals, which are bigger, flashier projects that ministers like to be photographed inaugurating.

Another big decision to make: are we going for a unified healthcare system model along the lines of the United Kingdom, a single-payer model, or some hybrid.

The Pakistani system as it stands right now consists of two completely separate systems. There is the government-owned, publicly funded system of hospitals and clinics, which are theoretically free or else highly subsidized to anyone who needs them. And then there are the privately owned hospitals and clinics, most of which operate on a for-profit basis, and charge on a fee-for-service basis to anyone who has the ability to pay their charges.

Until recently, the two systems were not linked, but with the introduction of the Sehat Insaf card in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, the Punjab Health Initiative, and the National Health Programme, the two systems are about to become more closely connected.

Take the Sehat Insaf Card, for instance. Under the programme, any eligible household in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (and over half of all households in the province are eligible), will be given a card and allowed to spend up to Rs540,000 per year per household on any care they need from designated private hospitals as well as any government hospitals.

That is a very generous system, at least by Pakistani standards. To put that in perspective, the average Pakistani household spends approximately Rs25,800 per year on healthcare. To provide an allowance that is almost 21 times that amount seems like a very generous initiative, and perhaps an invitation for use beyond that which might be necessary.

Because that is the thing with providing a benefit that is free for users: if they do not feel any of the costs, they will likely not stop themselves from using more than they need.

Punjab’s initiative is a little less generous, with Rs250,000 in an allowable maximum for hospital services, and Rs50,000 for secondary services, per household per year. Still, it dramatically exceeds what the average household actually spends in a given year.

One could argue that given how abysmally low spending on healthcare currently is in Pakistan, that perhaps these initiatives are necessary to boost access and lower costs to people who are clearly putting off care that they need. Still, some caution is needed when designing these programmes. As the contentious debates around healthcare in the United States demonstrate, once a benefit is given, it can be very hard to take it away.

……………………………..

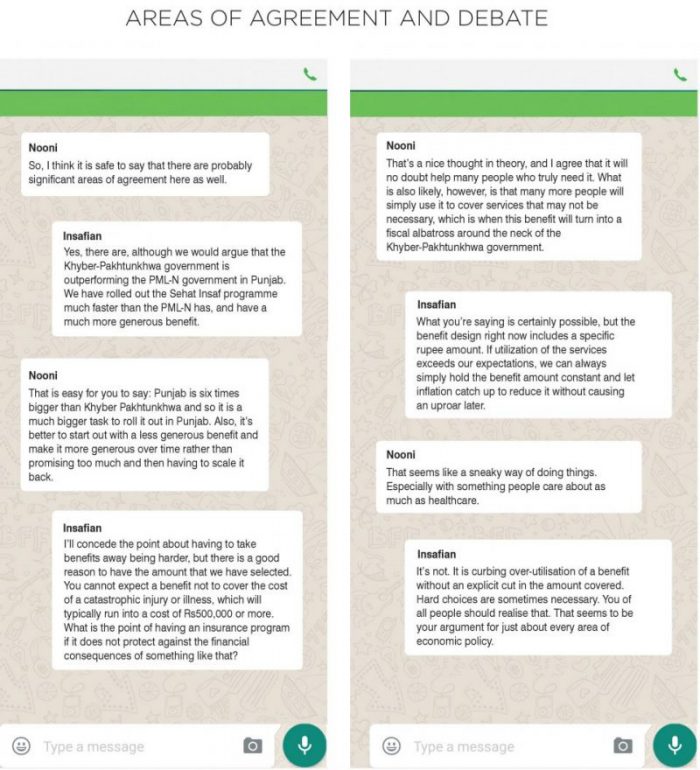

Areas of agreement and debate

Nooni: So, I think it is safe to say that there are probably significant areas of agreement here as well.

Insafian: Yes, there are, although we would argue that the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa government is outperforming the PML-N government in Punjab. We have rolled out the Sehat Insaf programme much faster than the PML-N has, and have a much more generous benefit.

Nooni: That is easy for you to say: Punjab is six times bigger than Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and so it is a much bigger task to roll it out in Punjab. Also, it’s better to start out with a less generous benefit and make it more generous over time rather than promising too much and then having to scale it back.

Insafian: I’ll concede the point about having to take benefits away being harder, but there is a good reason to have the amount that we have selected. You cannot expect a benefit not to cover the cost of a catastrophic injury or illness, which will typically run into a cost of Rs500,000 or more. What is the point of having an insurance program if it does not protect against the financial consequences of something like that?

Nooni: That’s a nice thought in theory, and I agree that it will no doubt help many people who truly need it. What is also likely, however, is that many more people will simply use it to cover services that may not be necessary, which is when this benefit will turn into a fiscal albatross around the neck of the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa government.

Insafian: What you’re saying is certainly possible, but the benefit design right now includes a specific rupee amount. If utilization of the services exceeds our expectations, we can always simply hold the benefit amount constant and let inflation catch up to reduce it without causing an uproar later.

Nooni: That seems like a sneaky way of doing things. Especially with something people care about as much as healthcare.

Insafian: It’s not. It is curbing over-utilisation of a benefit without an explicit cut in the amount covered. Hard choices are sometimes necessary. You of all people should realise that. That seems to be your argument for just about every area of economic policy.

This is a brilliant article focusing on healthcare reforms. I strongly believe that Pakistan should introduce a mandatory health care insurance program in order to ensure the each and every individual gets easy access to healthcare services irrespective of the costs involved. Such reform will also boost up private investments in the healthcare services bringing and adding competition towards service offerings.

Such reform will also boost up private investments in the healthcare services bringing and adding competition towards service offerings.This is a brilliant article focusing on healthcare reforms. I strongly believe that Pakistan should introduce a mandatory health care insurance program in order to ensure the each and every individual gets easy access to healthcare services irrespective of the costs involved.

I hope Govt will pay attention to medical health and will provide sufficient budget for the healthcare sector. Health reform is much needed as a developing country way back in the health sector.

That is a very generous system, at least by Pakistani standards. To put that in perspective, the average Pakistani household spends approximately Rs25,800 per year on healthcare. To provide an allowance that is almost 21 times that amount seems like a very generous initiative, and perhaps an invitation for use beyond that which might be necessary.

Comments are closed.