It started, as all things seem to these days, with a twitter trend. #LUMSFeeHike climbed the national twitter trend in Pakistan in a matter of hours, reaching the top trend position overnight. The reason? A 41% hike in fees that had the student body in uproar.

The university submitted a tacit admission of the new policy that has led to the increase in fee in the form of a clarification, to try and mitigate yet another public relations disaster led by its own students. However, the uproar grew as leading faculty members from the university joined the virtual protest instigated by the students of the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), urging the institution to reconsider.

At a time when universities everywhere are already under scrutiny for charging their students the same amount in lieu of tuition fees, even though their operations have gone online, the impact of such a large surge has a number of people reeling. And with campuses closed, the only way to protest the move has been through social media, where the students and faculty waged a battle against the administration.

The nature of higher education, much like most things in the post pandemic world, are changing and will change for good. But as things stand, universities are at a point where they know as much as the next person does. Video Conferencing solutions such as Zoom and Webex have thrown them a lifeline, but the level of engagement in and quality of lectures has been a far-cry from a classroom environment.

Once the uproar got particularly loud, LUMS was forced into a more detailed explanation highlighted in an email from the university’s Vice Chancellor, Dr Arshad Ahmad, which claimed that the restructuring of the fee system was to ensure students do not overburden themselves with too many course credits, and that the 41% calculation was overestimated. But the rebuttal has left both students and faculty feeling that the new system will establish an unfair hierarchy within the university that will advantage students with more means to artificially improve their GPAs and transcripts.

By the university’s own admission, the move to change their fee structure and in the process increase it had been a decision that had been on the cards since well before the pandemic hit. While LUMS has been using this as a defense, it is a condemnation more than anything else. Academia, for all of its high-horsed posturing and talk about ‘caring’ about students, turns into a shockingly bureaucratic, pencil-pushing clique when professors and educationists make the switch to administration.

Universities, more than most other industries, cannot go on as though the pandemic never happened. Their plans, much like the plans of their students, must be adjusted to accommodate new realities. This is not just something that applies to LUMS. Higher education across the world has had a rude wake up call, and will need to make significant adjustments if they are to survive this brave new world unscathed.

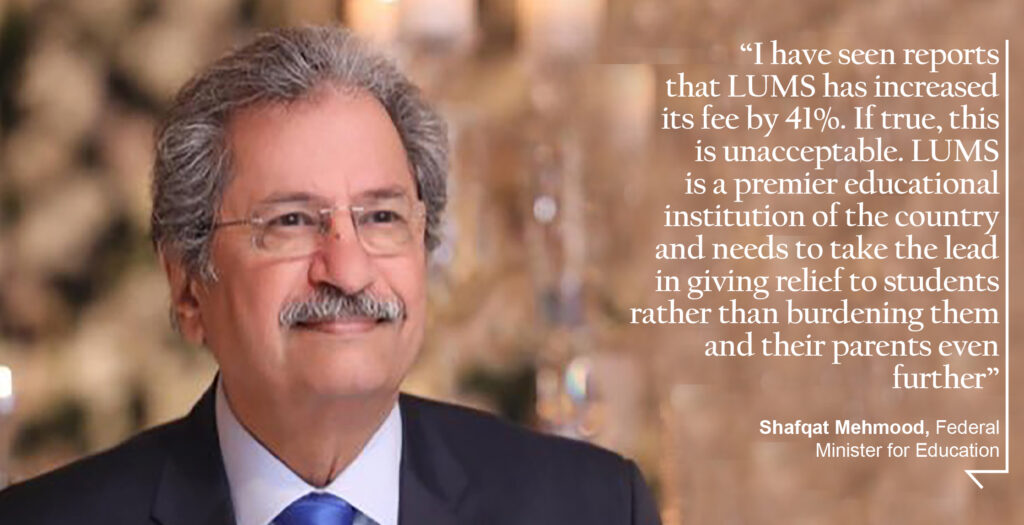

The entire online fiasco surrounding LUMS went so far as to garner the attention of the federal government, with Education Minister Shafqat Mehmood fittingly also taking to Twitter to condemn the apparent price hike of 41%, declaring that the move was unethical, particularly in the middle of a pandemic, and that the university should reconsider.

It is notable that it was not the student or faculty protests but this attention from a federal cabinet minister for LUMS to send out another detailed explanation, which once again repeated the same talking points, but with the additional promise to grandfather existing third and fourth year students out and let them continue on the old fee scale and charging system.

While Shafqat Mehmood’s stern Twitter reprimand did cause the university to scramble and make this important concession, it has still not gone back on the move, or answered questions about the implications of what such a system would mean. It also leaves a lot of other questions unanswered, such as how the higher education system should be reacting to the pandemic, and the extent to which it can expect to change the fee structure for students quite so dramatically in the middle of their degree programs at a time when many families are significantly financially constrained.

The numbers

Let us start with a disclaimer, because with the name LUMS come many associations. The private university has a hefty price tag, with a degree costing up to Rs3 million for a four year undergraduate programme. And while this gives rise to sneers and jeers that those attending all belong to the economic ‘elite’, there are those in the university that are not on financial aid or scholarships, who still have parents scraping by to pay the hefty fees. Education is supposed to be a path to climbing the social ladder, which is why people are willing not just to pay but to invest in an education from an institution like LUMS.

LUMS, like many universities, works on a credit-based system. Students take between 12 and 20 credit hours in a regular semester, and must complete 130 credits to graduate on time in four years. This would mean that students take 16 credit hours most semesters and 18 credit hours in any one semester. However, the fee for 12-20 credit hours is a blanket fee, and you pay the same no matter how many credits you end up taking on. Under the new fee system, LUMS is charging per credit hour, which would mean taking on 20 credit hours would cost far more than taking on 12 credits.

Based on this method, students that took 12 credit hours in a semester found its courses to be more expensive compared to students that took the maximum allowed, that is, 20 credit hours. The LUMS administration argues that this “cushion” resulted in students taking more than the required course load.

They say that it “…incentivized some students to take course overloads each term.” Many of these students were not able to handle these overloads and took more credit hours than was required by their degree programs.

However, the new method removes such a “cushion” without fair warning leaving students that intended to take the maximum number of credit hours at loss. The university, however, claims that the decision of the per credit hour fee is based on 16 credit hours, and not the minimum 12, thereby resulting in negligible difference for a student taking 16 credit hours, a decrease if taking 12, and an increase if taking 20.

While the university claims that this is only a 13% increase in the fee, the impact on students is greater in the case of more credit hours and results in an approximate 40% increase in the fee over a semester if a student chooses to take 20 credit hours. While the 13% increase is on the per credit hour fee, it does not hold throughout different levels.

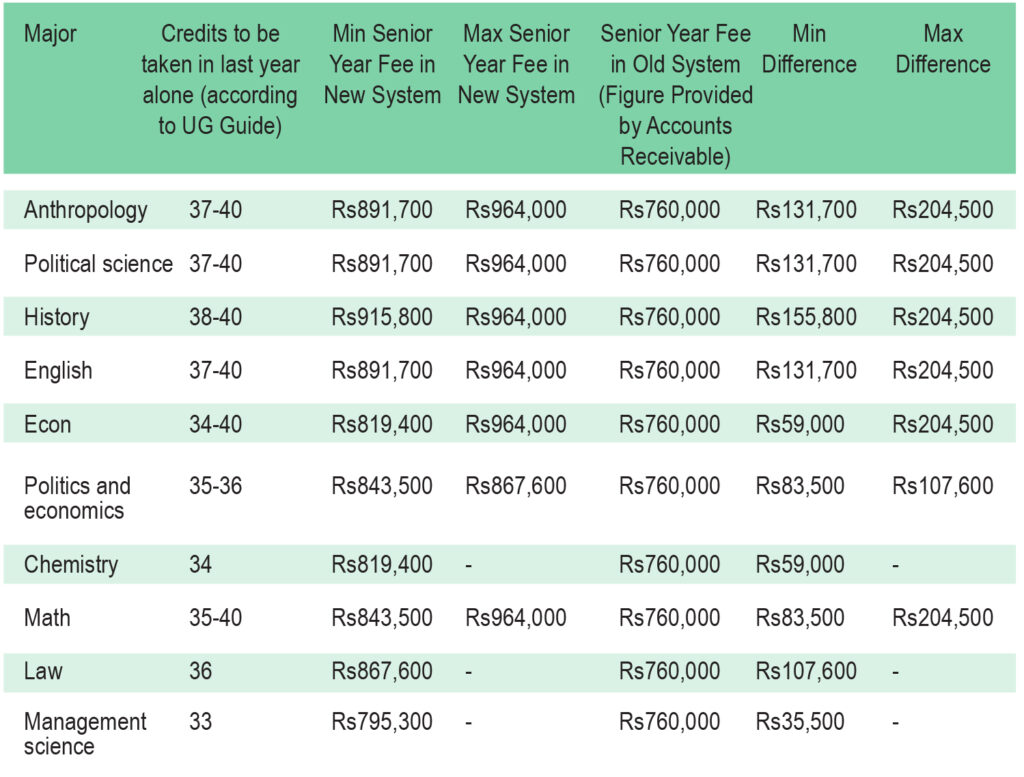

According to a table calculated by the LUMS student council in their correspondence with the university administration, the minimum and maximum difference per year are expressed in the table below.

It is important to mention at this point that LUMS continues to deny that there has been a 41% price hike. The way they have denied it is legally correct, because there has not been a blanket increase of 41%. Instead, there are certain students who will be more disadvantaged, particularly those who have had to retake courses or have changed their schools or discipline somewhere along their academic career.

The conundrum

Profit made many attempts to reach out to the university, the closest we have come to a response are empty emails from the Vice Chancellor, Dr Arshad Ahmad, who continued to simply respond with a passive aggressive manner and without any clear answers to our questions. LUMS did, however, send multiple statements and press releases on the issue. One addressed to the media read, “There has unfortunately been significant misinformation on social media, and it is important to clarify that students at LUMS will not pay any more than what they had committed to pay. In fact, some will actually end up paying less.”

The first important concession here is that existing students will be grandfathered out of the system and not have to pay more than what they agreed upon when joining the university. It must be pointed out that this concession came only after Profit contacted federal education minister, Shafqat Mehmood, who said he would look into the issue and then tweeted about it. More importantly, the grandfathering is only for one batch of students, and at least two other batches will be unfairly affected.

There are a few other things that remain unanswered, which Profit once again reached out to Dr Arshad for comment, who continued to evade the topic at hand. The response which Profit received from Dr Arshad was missing the two most important questions, the first being, even if this was planned earlier, is going ahead with the change in fee structure during a pandemic the right call? Would the new system not be such that students with more means would be able to repeat courses and take more courses, thus creating a hierarchy within the university?

These are, of course, uncomfortable questions to answer. Dr Arshad is a respected educationist and academic, but his actions in the entire situation have been viewed by many students and faculty as unhelpful to students. LUMS has often taken pride in having an effect outside of its walls and all over Pakistan. A tone-deaf change in the fee structure with these repercussions is unlikely to have the kind of impact that LUMS might find desirable on the wider higher education sector in Pakistan.

What universities should be doing

In a recent article for Dawn, Ahmad Ahsan, a development sector professional and alumnus of Texas A&M University, has argued that the pandemic is a chance for universities to turn a new leaf in Pakistan, and for the Higher Education Commission (HEC) to become a strong and credible institution. It is also a time for universities to become empathetic and trust their students, instead of blinsiding and in certain instances gaslighting them.

Unfortunately, all contact with the HEC for the purpose of this story has been fruitless. From a director level up to the chairman’s office, there was little knowledge of the LUMS fee hike let alone any sort of discussion on bigger picture scenarios, a shocking level of apathy at a time of transformation in the sector that the HEC supposedly regulates.

According to a study by the World Economic Forum, WEF, “The pandemic that has shuttered economies around the world has also battered education systems in developing and developed countries. Some 1.5 billion students — close to 90% of all primary, secondary and tertiary learners in the world — are no longer able to physically go to school.”

What is clear is that these are unprecedented times. The massive shift to online education is perhaps one of the greatest disruptions that we have seen because of this pandemic. And while universities must sputter on somehow, they clearly do not know just quite what they are doing yet. This is new for everyone, which is why it is so important for universities to scrap any of their old pans, and guide their students and faculty through it step by step with a hold-their-hand approach.

What we have seen in this one episode is an administration getting aggressive and condescending with a student body thrown into a serious crisis. Even if the change in fee system had not been shocking, what was surprising was how the student body was taken into confidence only long after they had to rage about it on social media.

This will not be enough anymore, and if physical contact is to remain elusive for the time to come, universities need to get much better about their communication with the students, faculty, and wider university communities that they are the stewards for.

Otherwise, with the amount of disconnect already facing students, there will be nothing but chaos and discontent. But one thing is certain: at a time of tumultuous change, when leadership was required of LUMS to navigate on behalf of the nation’s higher education sector, the university’s leadership was found wanting. Other universities, whatever they do, must not do what LUMS has done.

Comments are closed.

Entry test and admission test date should b exceed at any cost.

That’s the reason IBA is better. LUMS talent pool is among the rich elites who afford to pay such high fees. So lets say in our country, 50000 families can afford to pay that high fee for their kids interested in pursuing management sciences. Many of them would have their kids study abroad. Out of remaining, those who pass LUMS test gets selected. For IBA, that talent pool is considerably higher and hence theoretically, better quality and more talented students get selected in IBA, compared to LUMS.

However, the teaching methods and quality of teachers in LUMS are far superior than that in IBA (although IBA is catching up on that). But overall, the quality of students matters more as the brilliant ones don’t really need the teacher to gain proficiency, especially over complex subjects such as Finance, Maths, Accounting etc.