When the coronavirus pandemic was at its peak in Pakistan, one of the first industries that Prime Minister Imran Khan insisted be given relief and allowed to open was construction. Construction has been at the heart of the Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) government’s agenda since it came to power in 2018.

From the ambitious Naya Pakistan Housing Scheme to the many projects of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and other construction activities, brick and mortar has been the government’s answer to uplift the economy. In fact, the Prime Minister showed just how important he considered construction when in April this year, he announced incentives for investors and businessmen as the government tried to mitigate the economic impact of the coronavirus outbreak.

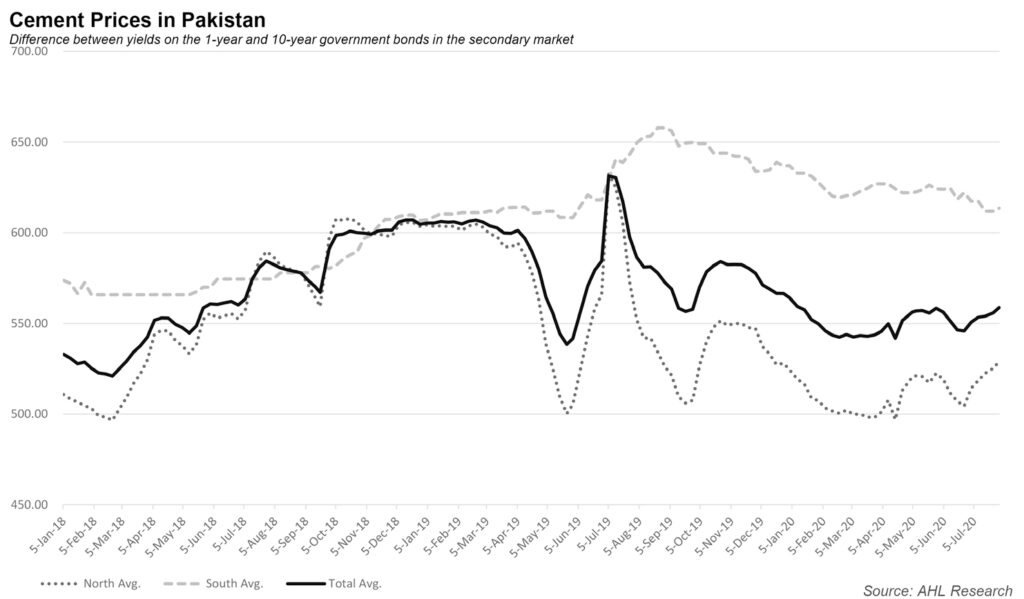

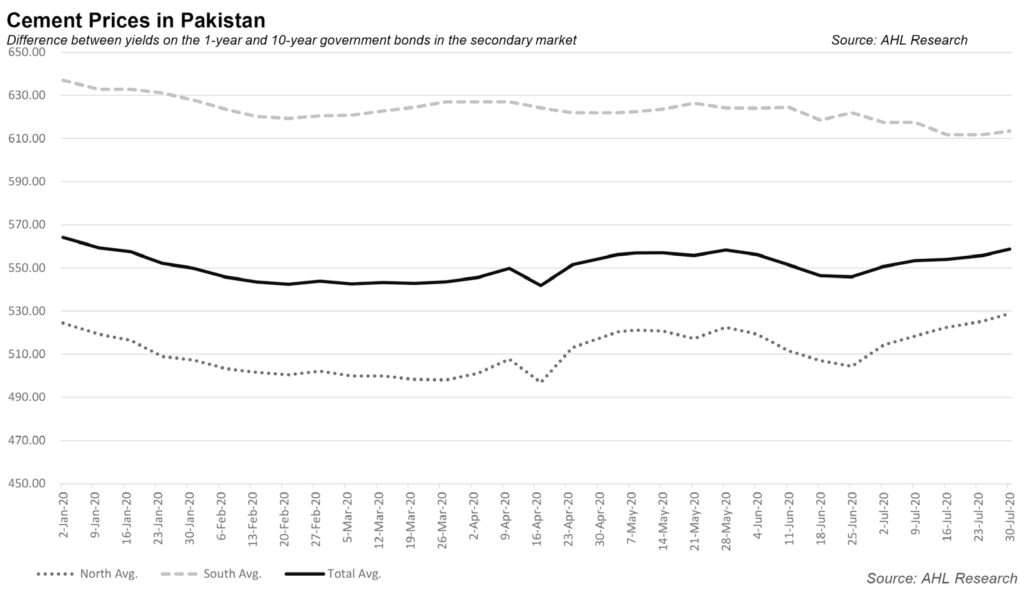

While it was not a surprise that construction was favoured, one of the sectors involved in construction that has been most active since the reopening has been cement. Its retail prices in the north region have increased on average by 4.62% from Rs497 per 50-kilogram bag in April to Rs520 in May according to data released by Arif Habib Ltd (AHL).

A similar rise was noticed again in July, after the Prime Minister announced major construction projects and provided a subsidy of Rs30 billion for the Naya Pakistan Housing Project so that people could build their dream house at an affordable cost.

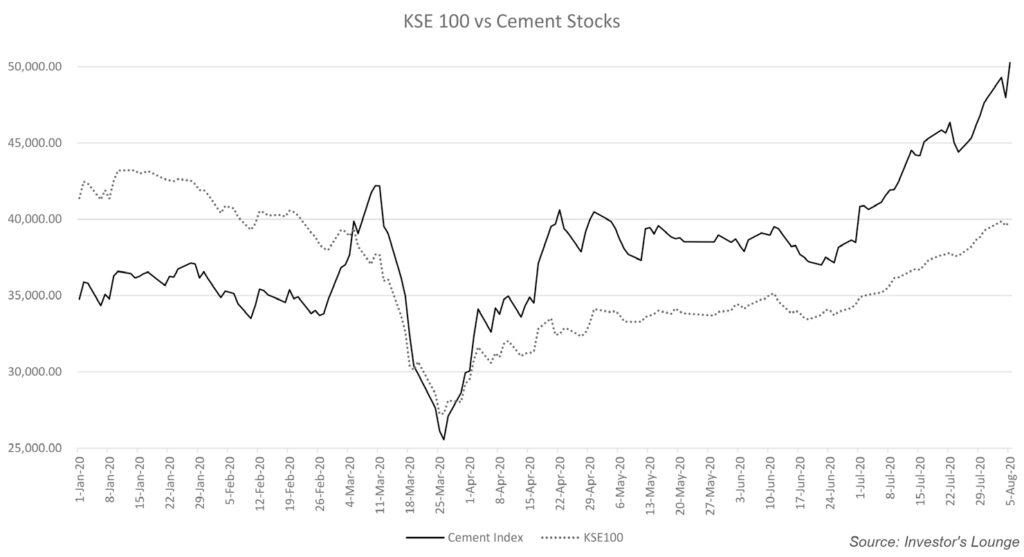

The increase in the price of cement has caused a significant rally in cement stocks. The problem is that the fundamentals do not support such behaviour. The northern region of Pakistan, including Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, have specifically faced an increase in cement prices despite impotent statements by the Industries Minister Hammad Azhar, who asked them to reduce cement prices immediately.

Between June 25, 2020 to July 16, 2020 the price of a 50kg bag went up between Rs40 to Rs45 in the twin cities of Rawalpindi and Islamabad. This is the highest rise the country has seen cumulatively.

According to data compiled by AHL, the price of a 50kg bag of a cement on average went up from Rs511 on January 5, 2020 to Rs529 as of July 30, 2020 in the north, and in the south went up from Rs574 on January 5, 2020 to Rs614 as of July 30, 2020.

Shahrukh Saleem, an investment analyst at AKD Securities, was of the view that declining oil prices would result in a decrease in the cost of captive power generation for some players in the cement sector.

Such trends are nothing new. The cement industry has had a long and storied history of cartelisation and manipulating prices since way back in the 1990s. The Competition Commission of Pakistan (CCP) and the Monopoly Control Authority (MCA) before it have initiated numerous inquiries against it. With only a handful of players, the All Pakistan Cement Manufacturers Association (APCMA) has 15 members including Lucky, Askari and Fauji Cement, agreements within the sector have often borne classic symptoms of cartelisation.

The story of ‘quotas’ and rising prices to avoid competing fairly because of the nature of the industry is not a new one. But it may be repeating itself at a time when the federal government is going to need more cement than ever before. Which is why, before it all goes down, it may be useful to look at why the cement industry offers itself up to cartelisation, and how it has constantly gotten away with it.

A cartel history

In 2008, the newly formed CCP raided the offices of the APCMA. Along with bundles of other evidence, they would discover a 2003 agreement between members of the association, that essentially was an agreement to form a cartel. Since then, the cartelisation of Pakistan’s cement industry has been an on-and-off affair depending on the moods of the big manufacturers. But throughout all of it, no tangible action has been possible up until now.

But before we move on to this agreement and how the cement cartel is operating currently on shaky grounds, let us go back decades, to the beginning, before either the CCP or the APCMA even existed. Because cartelisation in the cement sector has existed since long before.

In 1992, Pakistan was struck with destructive floods and a major reconstruction undertaking was needed. What should have been a moment of national rebuilding ended up being overshadowed by an investigation by the MCA, which was taking an in-depth look into the distribution system, pricing patterns, capacity utilisation and cost structure.

MCA concluded that a cartel had been formed and made recommendations to the Economic Coordination Committee (ECC) of the federal cabinet. The recommendations were approved and State Cement Corporation’s units were directed to open their retail shops at important points in major cities and to sell the cement at the rate recommended by MCA and approved by the ECC. (Because, of course, what better way to handle a price-fixing scandal than with more price-fixing.)

While the problem was solved in the short term, this was a problem that would keep rearing its ugly head over the years. Six years down the road, in 1998, the price of cement was raised by all cement manufacturers in October 1998 through collective action – from Rs135 a bag to Rs235 per bag, an overnight increase of 74%. The MCA launched another investigation, and discovered that none of the input costs had risen and the increase in price was simply a result of cement manufacturers agreeing amongst themselves to increase the price.

When the MCA ordered that cement prices be reverted, cement manufacturers went to court and managed to get a stay-order. As a result, the government had to compromise to strike a deal with the manufacturers, which included ordering the authority to back-off from the cement sector.

This soon became a pattern, whereby prices would be increased for no reason, the MCA would intervene, and cement manufacturers would go to the courts and drag the case on for years, selling at their own chosen prices the entire time. This was the case in 2003, when prices increased by Rs35 per bag overnight. The court case that followed lasted for years, going deep into 2006, and even then the Lahore High Court (LHC) ruled in favour of the cement manufacturers on the basis of a lack of evidence, declaring that “conscious parallelism is not in itself sufficient to lead to or permit an inference that a price fixing agreement or cartel exists.”

As a result, the government had to begin providing a subsidy to the import of cement to counter the cartel tactics of local manufacturers by bringing down the prices of imported cement. However, the measure was a short-term one, and eventually only bled the government and ended up being expensive and doing little good.

Even though the prices came down gradually over the next 6 months, from Rs353 to Rs195 per 50kg bag in January 2007, in February 2007 they rose, quite suddenly, by Rs60, to a new high of Rs255 per bag. Again, what followed was predictable. The MCA initiated an inquiry, CEOs of different companies all said they were acting independently, and the authority once again failed to find any conducive evidence of cartelisation.

It seemed at this point that little could be done, even legally, about what the cement sector had been doing for nearly two decades at that point. It was perhaps fortunate that the Competition Commission of Pakistan was formed in 2007, and immediately took on cement manufacturers. However, the back and forth between the sector and the CCP has resulted in little tangible change.

In 2008, the CCP initiated its first move against the cement sector, carrying out a market study of the cement industry that was focused on their working. The main goal of this study was to assess whether the price rise that took place in 2007 due to cartelisation or, as the cement manufacturers claimed, spontaneous input price rises.

During the same period they also carried out a raid on the offices of the All Pakistan Cement Manufacturers Association (APCMA) for collection of evidence and subsequently conducted an inquiry into the matter.

The CCP ended up issuing show cause notices to 22 cement manufacturers including the APCMA for the unusual hike in prices back then. While speaking to Profit, sources from the CCP said that the inquiry brought to light the cartelisation of the cement companies and the predatory pricing that had taken place.

Eventually, two years later in 2009, the CCP issued a penalty of Rs6.3 billion on the members of the association. To this day, over the more than decade long existence of the CCP, the cement sector is the single most heavily fined market sector by the CCP. But this was not the last run-in between the CCP and the sector.

In 2012, a raid was conducted on the offices of the APCMA and the offices of Kohat Cement for unjustified rise in prices. However, once again, both organisations were able to gain a stay order and no further inquiries were carried out in the cement sector.

But what is the APCMA and what manufacturers does it consist of? More importantly, is it the linchpin that holds together the cement cartel?

Association or front?

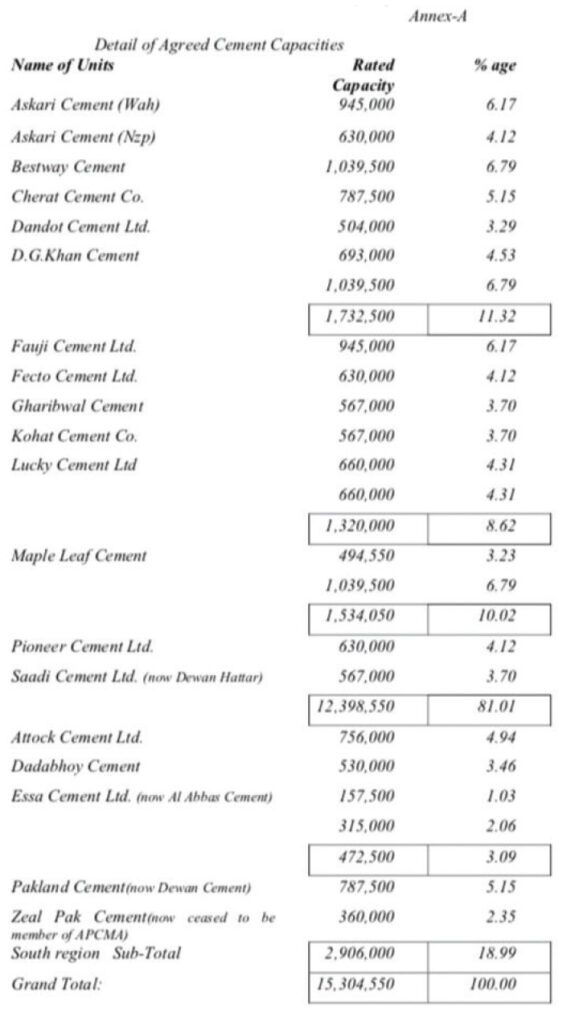

The All Pakistan Cement Manufacturers’ Association is officially a nonprofit industry association incorporated in 1992. As of now, the association has 15 members. Reaching a consensus between so many players is difficult, and for a cartel, the body seems rather bloated.

Essentially, its objectives include providing a common forum for the cement manufacturers; protecting, safeguarding and promoting the interest of its members; monitoring production levels of its members and thus, the industry as a whole; and coordinating and securing cooperation amongst its members.

This official description could be copy pasted from any association of any other industry. However, the question is, are they colluding unfairly? To get to the bottom of this, we must look at their membership agreement more closely. But where did this agreement come from?

The CCP has said that according to its study of the cement sector, the APCMA offers membership to all cement manufacturers operating in Pakistan, on the payment of a fixed entrance fee plus an additional annual subscription fee. The accusation that the APCMA was acting as a front that allowed the cement industry to act as a cartel had come to a head in March 2008.

On the 20th of March that year, a news item appearing in the newspaper Jang and on the website of Geo News revealed that the price of cement was raised by Rs15 to Rs20 per bag across the country, pursuant to a secret agreement. The CCP created a four person team that conducted the earlier mentioned raid.

As a result of that raid, the CCP recovered crucial evidence, including a crucial marketing arrangement entered into by the members of the association in May 2003. The agreement contains clauses such as the members using quotas and input prices to keep cement prices ‘desirable.’

The agreement

Moments where you can point out a mustache twirling villain are rare. But in the agreement that members of the cement association had signed, it was clear that it was nothing other than a cartelisation. In so many words, the agreement established supply quotas. The detail with which these were established was impressive almost.

A production quota is simply a goal for level of production, usually set by the government, but in this case agreed upon by manufacturers amongst themselves. By setting quotas for production, these manufacturers are able to set their own prices, whether higher or lower, not caring for their production capacity. It is through the framework of the APCMA that they have been able to set their own prices and manipulate price increases overnight.

In fact, this agreement went so far as to say that the decision of the chairman on the setting of quotas, with advice from members of the board, would be binding on all of the manufacturers. While some of these agreements are typical enough, the secretive nature of the document raised questions.

And as a result, in their 2008 study, the CCP concluded that the “point-in-time” view that this price hike “could be the result of change in sector fundamentals affecting demand and supply dynamics and due to commercial reasons” but that the Commission could not “rule out the possibility that this across-the-board, simultaneous price increase may have arisen from collusive behavior of the incumbent cement manufacturers”.

This particular case is still stewing in court, and the APCMA has regularly refused to comment on it or the 2003 agreement that was discovered. Even the current chairman of the association, Azam Faruque, refused to comment when Profit asked about the case.

Trouble in cartel-adise

The obvious question, however, is how do all these big manufactures with their own interest and egos all toe the line? The answer is: they don’t always do that, and the desire to cheat on the agreement is constant. Profit reported on June 25, 2018 that the APCMA also allegedly regulates prices, not allowing any company to sell at lower than the prescribed per bag price. So, the cartel’s survival depends on each of the companies adhering to the supply quotas and set prices. But the industry dynamic is such that the motive to cheat is ingrained in the companies.

“For instance, if one company quietly breaks away from the cartel and produces more than its allotted quota, it shall earn more and in the bargain capture a larger market share too. If, however, all or most of the companies decide to produce more than their quota their combined profitability decreases bringing the existence of the cartel under risk,” said one source within the industry.

A few manufacturers in the south, including Lucky Cement and Cherat Cement, set up new plants in 2018, and wanted their quotas enhanced. Since the quotas (which, by the way, are illegal) are decided on the basis of actual capacity, these companies needed to get these inspected and verified by the APCMA. However, some were reluctant to get their capacities verified.

A case in point is Muhammad Ali Tabba, the owner of Lucky Cement, who only allowed a two-day inspection, while the association said they needed at least a month to properly asses Lucky’s capacity. As the largest cement manufacturer in the country, Lucky can throw its weight around, and put the cartel nature of the industry through choppy waters.

The catch here was that there are ways to temporarily show a higher capacity by using higher quality inputs for a compressed period to make it easier for Lucky Cement to get a higher quota than what it would have landed otherwise.

In 2018, for example, the cartel was in shambles due to the expansionary trajectory in the industry as well as the unwillingness of the bigwigs to devise a mechanism. A battle of egos, so to speak, between industry leaders like Lucky and DG Khan Cement and others was indeed good for the consumers. However, now, as the construction industry picks up again, the rise in prices is indicative of the cartel being back to its old tricks.

Where we stand

According to research analysts at Arif Habib Ltd (AHL), an investment bank, cement sales in Pakistan hit a record high in July 2020 compared to previous months. This occurred in the midst of the global pandemic. Exports are also expected to soar to an all-time high of 900,000 tons.

According to the CCP, there has already been an inquiry into the possible collusion between the companies which has caused the rise in cement prices. The regional parity between cement prices is evident. The question is: what are the factors causing this parity?

According to the reports published by AHL research, the greatest rise of cement prices has been witnessed in Islamabad and Rawalpindi by 4%. Rise in cement prices has ignited a significant rally in the stock prices in Pakistan, with the bulk of activity in the cement sector stocks.

According to the official sources, senior representatives from the cement companies in the northern region met on April 22 and decided to raise the prices significantly despite a global decline in oil and coal prices. Cost increases were nonexistent and therefore do not justify such a rise in cement prices as has been seen.

In order to carry out a detailed inquiry into rising prices of cement CCP has asked companies to submit their costs from July 2019. The companies that have received orders to provide CCP with data include Bestway Cement, Kohat Cement, Attock Cement, Pioneer Cement, DG Khan Cement, Gharibwal Cement, Dandot Cement, Fecto Cement, Cherat Cement, Lucky Cement, Maple Leaf Cement, Fauji Cement and Flying Cement. These cement factories are primarily based in the Northern region.

Meanwhile, Yousaf Rahman, a research analyst at KASB Securities, a brokerage firm, believes that the cement industry is set to enter greener pastures from fiscal year 2021 onwards. The industry’s fiscal year runs from July 1 to June 30.

The sector will likely be able to weather the pandemic due to support from the government via the construction package. Moreover, the industry will likely benefit from lower coal prices and the 625 basis points (bps) reduction in interest rates, bolstering its profitability potential. “With large-scale projects such as the Diamer Bhasha Dam and the Naya Pakistan Housing Scheme gaining traction, we believe the industry is all set to benefit from a significant improvement in its pricing power, the key driver of the industry’s profitability,” wrote KASB Securities analysts.

But what will happen once the economy recovers and local demand goes up again? What will happen when massive projects like water reservoirs or Naya Pakistan Housing Scheme kick in? What will happen when allocations under the public-sector development programme gain momentum?

The answer is obvious: the cartel will rear its head once again unless reforms are swiftly carried out to prevent collusion. One policy idea is for the government to prevent further mergers and acquisitions in the industry, which has seen its membership shrink from 22 to 15, largely due to the larger companies acquiring the smaller ones.

The survival of the cartel shall for a large part depend on how well the demand matches the added capacity. According to industry experts, if the added capacity is more than the available demand, the cartel may break yet again.

Additional reporting by Ariba Shahid

Mr Naqvi, scan through the audited accts of cement industry, u will c almost all producers in huge losses. Coal, electricity, packing material, all gone up by huge percentage. Even 1st qtr 20/21 results too will be bad. Cement was selling in North back in 2017/18/19 at an avg of 580 a bag where as today it is around 490-510 in retail. Please research before penning down.

Dear Iqbal Sb, you need to check firs APCMA data before commenting on this article. You will find that our exports are much more than 2018-2019 and even in some cases more than last 3-4 years.