From the very beginning of its tenure, the go to word for Prime Minister Imran Khan and his government has been remittances. One of the Prime Ministers strategies to fix the balance of payments was asking expat Pakistanis to send dollars.

The sceptics, of course, laughed. And rightfully so to some extent. Fixing the balance of payments by asking the expat Pakistani population to send $1000 was the kind of fantastical solution that borders on silliness. But there is one truth to the matter – remittances are important.

Globally, there are 270 million people that work away from their home countries and send money back to the motherland. For a lot of developing countries, remittances have become a vital source of financing for many developing countries.

And as a recent NPR report has shown, the sums of money are huge. In fact, the amount of money sent in remittances is greater than the sum of all investments made by foreign companies in developing countries combined. And it is more than triple the amount of aid that governments provide those countries.

And ever since the incumbent government has come into power, remittances in Pakistan have undoubtedly increased, and significantly. And more importantly, the trend has continued despite the coronavirus pandemic, at a time when they were expected to go down sharply.

The government has been quick to claim credit for the increased remittances, but the trend is not true for Pakistan, but internationally. So why have remittances increased when everyone expected them to fall, both in Pakistan and abroad? Profit takes a look.

How important are remittances

Here’s how remittances work. Migrants working abroad send money to their families in their countries of birth. It sounds simple enough, and nearly a very micro-economic, domestic activity. But with 270 million migrants sending remittances globally, according to the earlier mentioned NPR report, in 2019, remittances hit an all-time of over $550 billion.

With a constantly growing migrant workforce in developed countries, the foreign exchange earned through remittances is a big deal for developing countries. In the financial year 2018-19, Pakistan earned $21.7 billion through remittances. This amount increased in the next year, with remittance rising by nearly $2 billion to $23.13 billion. So as far as remittances were concerned, Pakistan was on an uptick, and so was the rest of the world.

In 2019, global remittances rose to a record $554 billion. And even this number was up by 20% compared to 2016. So what’s behind that jump? According to Laura Caron, a specialist in development economics and a consultant at the World Bank, one of the easiest reasons to pick up on is that countries that usually attract migrant workers have been doing well, and have seen growth.

“Part of it can be attributed to growth in the United States and also increasing flows coming from the Gulf Cooperation Council countries and from Russia as well,” she says. So essentially, because there was greater economic growth and activity in these countries, migrant workers were either making more, or more of them were getting work.

“There are a couple of other factors too. Another big push that’s causing this increase in remittances may be the boom in the use of mobile money and online or digital finance providers. So it’s getting easier and easier to send money home digitally.”

This point mentioned by Caron in her NPR interview is particularly pertinent in regards to Pakistan. Traditionally, Pakistanis have been carrying their cash back to the country in suitcases. The formalising of banking channels and the tightening of informal money markets has meant that more remittances are also possibly being recorded. In fact, this has actively been encouraged by the State Bank of Pakistan actively.

In recent times, the SBP has emphasised an orderly ‘market-based’ exchange rate management and sound policymaking under the Pakistan Remittance Initiative. The SBP sheds the spotlight on the reduction of the threshold for eligible transactions from $200 to $100 under the Reimbursement of Telegraphic Transfer (TT) Charges Scheme. It also stressed on adoption of digital channels and targeted marketing campaigns to promote formal routes.

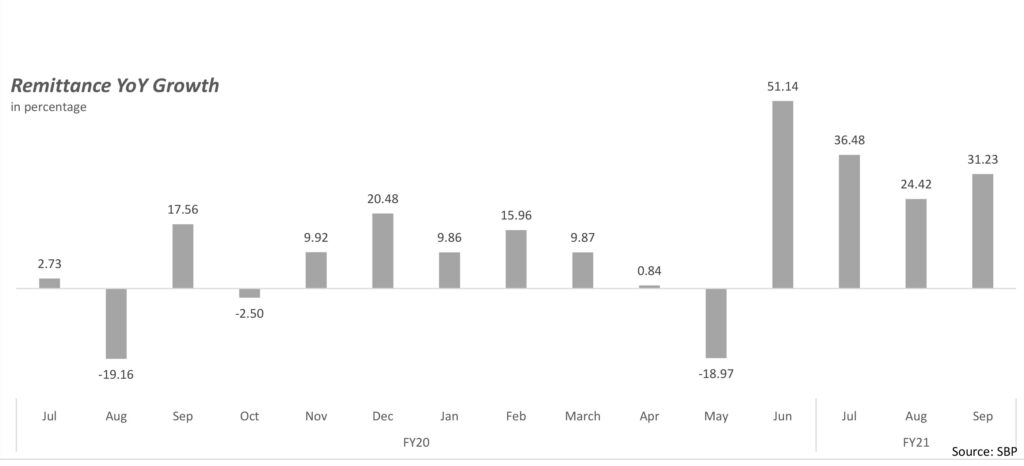

The increase in remittances in Pakistan and all over the world has been a noticeable trend since at least 2016, and it was expected to stay that way. Of course, that is when the coronavirus pandemic struck, and people prepared for the best.

The pandemic factor

When the coronavirus pandemic hit and triggered a global recession, it was being dubbed as the worst economic downturn since The Great Depression of 1929. With such bleak prospects, unemployment on a massive rise, industry coming to a halt, and general uncertainty, the World Bank predicted that global remittances would shrink by more than 20%. But that hasn’t happened. Recent data shows that remittances have held steady and in some cases, even gone up. One of those cases has been Pakistan.

According to Caron, on a general level, it is entirely possible that most migrants did not lose their jobs precisely because migrant workers are often essential workers. There is also the possibility that qualified migrants who were not allowed to work in certain sectors before, especially essential sectors like doctors or nurses, are now being allowed to work in those sectors as part of the pandemic response.

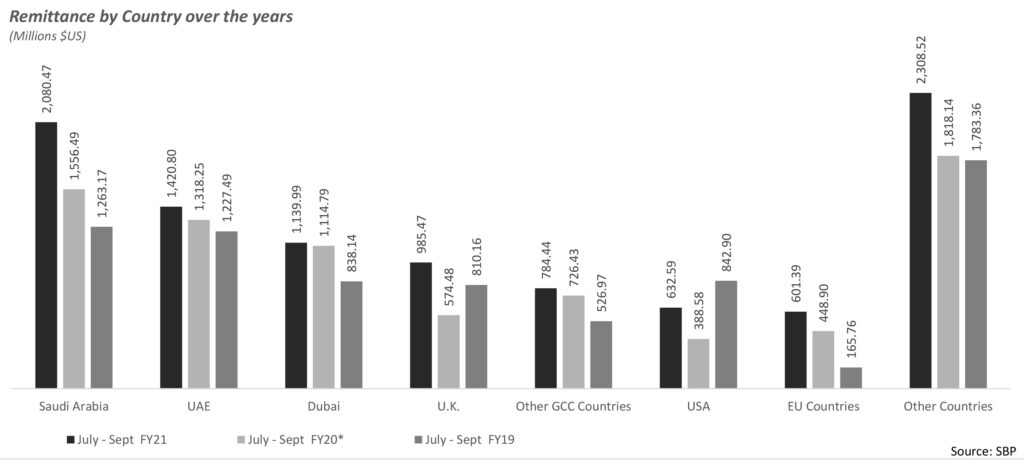

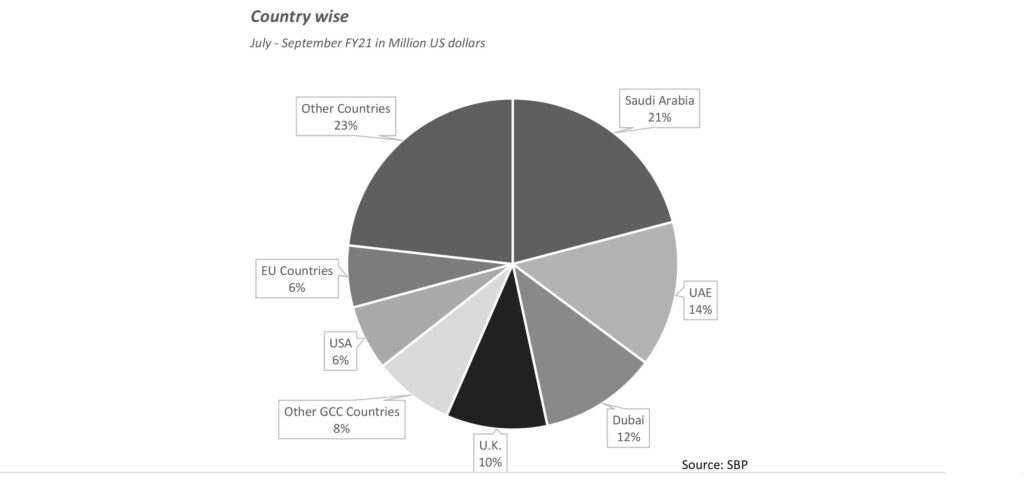

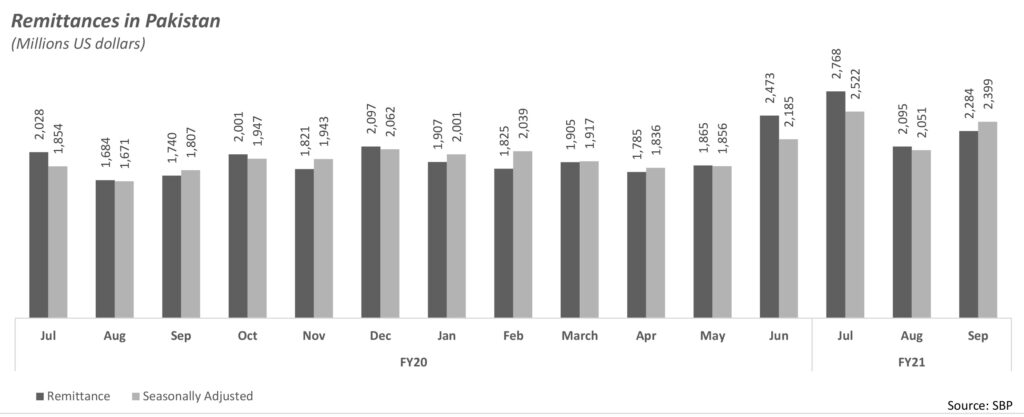

But this can only be one small explanation of where these steady, and in other places increased, remittances are coming from. Pakistan happens to be one of those locations where they have actually increased. In the July-September quarter of the financial year 2018-19, the total remittances coming into Pakistan were $5.54 billion. The following year, in the July-September quarter of 2019-20, the total remittances were $5.45 billion, indicating a slight fall in this quarter even though overall remittances increased by nearly $2 billion for the year, as mentioned earlier. However, the July-September quarter for the current financial year of 2020-21 has risen significantly to $7.15 billion.

There are a few major takeaways from this. First, the July-September quarter has seen a rise in remittances of around $2 billion compared to this quarter in the preceding two years. The increase is almost as much as the increase the entire year 2019-20 saw compared to 2018-19. Clearly this increase in remittances is not an everyday affair, and significant enough to wonder where all of this money is coming from.

Why have Pakistan’s numbers risen?

Back in June, when Pakistan was seeing the worst of the coronavirus pandemic, Workers’ remittances surged by a significant 50.7 percent in June, to reach a record high of $2.466 billion compared with $1.636 billion in June 2019. Surprisingly, the inflow of remittances from Pakistani diaspora saw an increase of 7.8 percent during the March-June 2020 pandemic period compared to the corresponding period in 2019.

Initially, this increase confused analysts, and most chalked it up to the upcoming Eid-ul-Adha holidays. Faizan Ahmed, head of research at BMA Capital, said the numbers were “fantastic and surpassed expectations.” However, he also ascribed the numbers to the upcoming Eid holiday. “I don’t think such high numbers will persist in coming months as COVID-19 continues to stifle world economies.”

His prediction proved to be wrong, and remittances continued to rise. The SBP said in a statement the significant increase in remittances during June 2020 could be attributed to a number of factors. Since many of the countries eased lockdown in June, overseas Pakistanis were able to transfer accumulative funds, which they were unable to send earlier. “Further, it is also believed that they sent remittances to support extended families and friends due to COVID-19,” the central bank said.

The last point is also one of the explanations that Caron offers is the altruism of the migrant worker. According to this theory, since migrants go to foreign countries to improve the lives of their families back home, it is possible that they are simply being austere and cutting down from their own lives to be able to send more.

The data on this is also clear. When things are bad at home, that is when migrants send back the most money, and corona has definitely hit the home countries badly economically, including Pakistan. This is the sort of explanation that the federal government would want to give.

That this significant increase in remittances is a result of the hardwork and selfishness of expats working to send precious dollars to Pakistan, giving the country much needed foreign exchange and a way to get out of its balance of payments crisis.

Caron actually backs this theory to an extent. “It has been established in migration literature that remittances tend to rise when things are bad at home,” she says. “So you would expect remittances to fall when things go badly, but instead, they rise. And that really gets to the heart of what migration is about. It’s about providing for their families as best as possible, even though they’re struggling in their destination countries.”

In addition to this, there is also the possibility that a lot of migrants are currently benefiting from government assistance. In some cases, like in the United States, the government has given cash stimulus packages to people, with cheques going directly to people. Not only have some studies shown that this has played a part in increasing remittances, but in places like California, even illegal and undocumented workers have been allowed to collect stimulus cheques. If these migrant workers are still working, they can simply send the stimulus cheques as they are to their home countries.

The flipside

However, there is a more sinister possibility as well, one that may have caused a spike in remittances for the time being, but could be disastrous in the long-term. This is the possibility that because of the pandemic and the nature of its spread, that a lot of migrant workers could be coming back home.

Why? Well, either because they have lost their jobs and cannot find any other work or because their host countries are turning migrant workers back to their home countries because of rising coronavirus cases. So why would that mean rising remittances? Well, if migrant workers are coming back to their homes without any knowledge of when they might get to go back, they will probably be sending a lump sum of savings ahead of them back home.

Even if they are staying in their host country, it is possible that they are sending these large amounts of money now because they have lost their jobs and do not know when it will be again that they will find work. If this is the case, they are again sending savings, and may be on thin ice. The problem is, none of us know how long the pandemic is going to last, but we do know it is not going away anytime soon.

As NPR points out, as the pandemic grinds on, many migrants must be finding it harder to find work. Even if they were in these insulated professions to some extent, if they’re essential workers. And, you know, living in the U.S. is really expensive, so people here must be thinking about going back to their countries of origin right now. And as Caron pointed out, this may be causing the upwards tick.

“When they decide to move back home, they might send ahead all of the rest of their savings that they had saved up for their lives in the destination country. And that might be causing a really big boost in remittances as people are sending back the money before they leave.”

Essentially, overall remittances have remained stable because of all of the reasons discussed above. But in places like Pakistan where there has been an uptick, there could possibly be less than ideal reasons for the rise. With all of this going on, and it being impossible to tell how long the pandemic will go on, whether remittances will maintain this trend or not, seems unlikely. Especially in Pakistan.

Excellent indepth research. Well done Abdullah.

One key factor in this article has been ignored and that is the impact of Covid on the informal “Hawala” remittance business. During the period April thru August there was severe travel restrictions (both domestic & International). Though formal data may not be available but one can not ignore this factor

The slow but steady legal interventions by govt are discouraging informal channels that’s one of the reason